The History of Cozumel

Editor's Note: Author Ric Hajovsky has been researching and writing about the archaeology and history of Cozumel for over forty years and has published several books on the subjects. He has found out some very interesting information about the history of Cozumel, and share his findings in his newest book, The True History of Cozumel. This article gives you a taste of what is in the book. The book comes in three versions: a 342-page, 6x9 paperback with full color images, a less expensive, black-and-white edition and of course, a Kindle version... all of them available from Amazon, of course. We hope you enjoy this bit of history of the Yucatan Peninsula!

****

The True History of Cozumel

The history of Cozumel has been hijacked by hacks. The story of Cozumel’s past is now almost completely obscured by the misstatements, mistakes, and misunderstandings put forth in hundreds of poorly-researched websites, misleading tourist brochures, and books by well-intentioned-but-clueless authors who relied on badly translated, modern English versions of edited and “corrected” versions of the original Spanish manuscripts as their primary sources.

For a few years now, I have been crusading against this dreadful process, because I hate to see the true record of the past slip away and be replaced by this new “Disneyfied” version of events. After writing articles on this subject in Spanish for various Quintana Roo newspapers and magazines, as well as giving talks at Cozumel’s Museo de la Isla and the Universidad de Quintana Roo, I decided to write a book about it in English. In the book, I tackle some of the most diehard myths and legends that have been touted for years as the truth regarding Cozumel’s past. Some of them have been repeated so often that they have completely supplanted reality in popular belief. Just two of the dozens of the more common tall tales about Cozumel that I address in the book are:

-Jacques-Yves Cousteau put Cozumel on the map when he made an underwater documentary on Palancar Reef in 1958. (or 1959, 1960, or 1961, depending on which website you read.)

-Ix Chel was the Maya goddess of fertility and there was a temple dedicated to her on Cozumel that all Maya women were required to make a pilgrimage to at least once in their lifetime.

Seeds of Truth

A few of the myths about Cozumel have a seed of truth in them, while others are completely made up. Take for example the first tall tale mentioned above, the old story about the Jacques Cousteau underwater documentary of Cozumel.

There are hundreds of websites that boldly state Jacques-Yves Cousteau was single-handedly responsible for bringing Cozumel to the world’s attention by filming a documentary on Palancar Reef around the end of the 1950s or beginning of the 1960s. As far as I can tell, this is a complete fabrication. There was no such documentary. The rumor began as a figment of someone’s imagination, or wishful thinking, or a misguided attempt at promoting tourism by associating Cozumel with the famous celebrity. It was then repeated and re-repeated. After years of reading about it, a kind of herd mentality has overtaken the public and most people will swear it is true. I can’t tell you how many Cozumeleños have sworn that their father, grandfather, cousin, or friend of a cousin was Cousteau’s dive guide during the filming of this phantom documentary.

However, any kind of serious search for kinescope copies, videotape, VHS tapes, DVDs, or written records of this purported documentary turns up nothing. Likewise, there are no newspaper articles of the period reporting on what must would have been quite a show, if it had taken place. Imagine the Calypso anchored off of San Miguel, handsome French divers coming ashore and posing for photographs in their spiffy striped t-shirts, and the big man himself, standing in his red tuque next to a proud Presidente Municipal for a hero shot. But no such photos exist and there are no contemporary newspaper or magazine articles that mention anything of such an event. Even the Cousteau Society themselves say it never happened. This oft-told tale is nothing more than one writer copying another without checking the facts and then being copied himself by another writer, and so on ad nauseam.

Le Monde du Silence and Cardona's Reef

I suspect that the source of this rumor had something to do with Jacques Yves Cousteau and Louis Malle’s 1956 movie Le Monde du Silence. This 1-hour 23-minute documentary (which had the same title as the book published by Cousteau and Frédéric Dumas in 1953) was filmed in the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and Indian Ocean. None of it was filmed in Mexico.

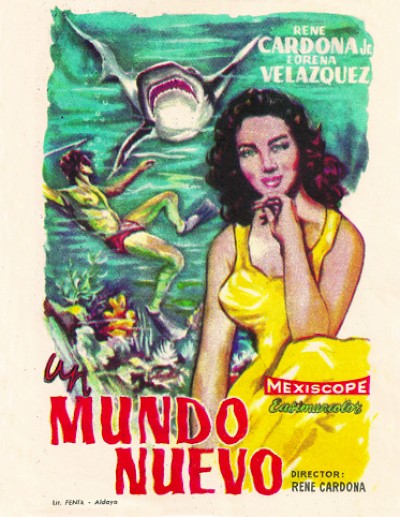

This Cousteau film did impact Cozumel, in a way, as it was the inspiration for director/producer René Cardona’s 94-minute movie Un Mundo Nuevo, which was filmed under Cozumel’s waters in 1956 by the American cinematographer Lamar Boden. (Boden would later be the cinematographer for the Sea Hunt series starring Lloyd Bridges and the movie Flipper.) Cardona was in Cannes for the premier of Cousteau’s film and realized there was a quick buck to be made if he rushed back to Mexico and shot a low-budget knock-off that could ride on the coattails of Le Monde de Silence. So, that is exactly what he did. It did not have much of a plot and the script scarcely filled a few pages, but it was Cardona’s film that put Cozumel on the divers’ map. And that, folks, is why we have a reef named Cardona Reef in Cozumel and no reef named after Cousteau!

Released in Mexico City on August 7, 1957, Cardona’s film played in theaters all over Mexico before being dubbed in English and released in the United States in 1958 as a TV movie under the title The New World. That same year, an article about Cozumel appeared in the May 1958 edition of Holiday Magazine (a Curtis publication for the American Automobile Association, at the time). It was written by John R. Humphreys and entitled “Bargain Paradise Revisited.” Over three million subscribers to the magazine read his praise of the island and the rush for a vacation in a tropical paradise was on.

While Jacques Cousteau did produce several TV series and documentaries, his very first series, The World of Jacques-Yves Cousteau was not made until 1966. No Cousteau-made documentaries, TV specials, or series that contained footage shot under waters anywhere near the Yucatan Peninsula were aired until the 1970s, more than a decade after the diving industry in Cozumel had become firmly established.

Ix Chel: A Myth Born of Misconceptions

For the past century, the Mayan goddess now known as Ix Chel has been touted as the patron goddess of Cozumel, the goddess of fertility whose sacred temple on the island was a center of pilgrimage to which all Maya women were required to visit at least once in their lives. Most people whole-heartedly believe these statements without question. I did, too, until one day I decided to look more closely into the subject. I searched the archives for the earliest mentions of the religious practices of the Maya of Cozumel and read them with a fresh eye. I was dumbfounded with the differences I found in the original sixteenth-century texts and the “new, modernized, and edited” Spanish versions available to the average reader and even more dismayed by the differences between the originals and the published English translations.

First, out of all the extant documents that were written prior to the twentieth-century, ONLY ONE contains mentions of both Ix Chel and Cozumel in the same text. All the other Spanish, Latin and Mayan documents speak of different gods and their temples on the island, but glaringly omit any mention of the goddess. And although this single, solitary document (written in 1579 by Diego Contreras Duran, a Spanish resident of Valladolid) links Ix Chel with a story Contreras had once heard about a temple in Cozumel, it says nothing at all about women making any kind of pilgrimage to it.

How A Myth Was Born

So, where did this whole myth about a women’s pilgrimage to the temple of Cozumel’s goddess of fertility begin? By tracing back the mentions of her in the literature, I found that prior to the 1920s, there was no link made between Cozumel and Ix Chel. Indeed, several pre-1920 archaeologists, anthropologists and historians claimed that the most famous Maya temple on Cozumel was one dedicated to the male god Teel Cuzam. And, although several early accounts mention a pilgrimage to Cozumel to make sacrifices of the bloody, beating hearts of dogs, deer, men, women, children and old people to the various temples and gods on the island, they all used the terms gods and temples in the plural and none of them associated women with the pilgrimage to make those grisly sacrifices.

A pilgrimage to a temple of Ix Chel on Cozumel was not mentioned again until 1924, when Samuel Kirkland Lothrop wrote a line about Ix Chel in his book, Tulum. “To her shrine on Cozumel pilgrims flocked from all parts of Yucatán and even from distant Tabasco,” Lothrop boldly stated. We assume that he took the idea that this temple belonged to Ix Chel from the 1579 written testimony of Contreras, but we do not know for sure. Lothrop did not quote his source for this tidbit. Note, however, that Lothrop also did not mention anything about women making that pilgrimage. His informants for this idea of a pilgrimage were the Spanish historians Diego López de Cogolludo and Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, but neither of them ever put forth the theory that the pilgrims to Cozumel were going there to visit a specific temple; that is something Lothrop came up with on his own. On the contrary, both early historians (as well as Bishop Diego de Landa) say the pilgrims to Cozumel were visiting multiple temples and making offerings to multiple gods.

Thompson Steps In

In 1939, the archaeologist John Eric J. Thompson published a scholarly article in which he put forward the same theory as Lothrop: that the most important temple on Cozumel was the temple of Ix Chel and it was the reason for the pilgrimage. However, Thompson used only the Contreras 1579 letter as support, along with a quote from the book of López de Cogolludo, in which Thompson inserted the name "Ix Chel" into a line of text, when her name did not appear in that line in Cogolludo’s original manuscript.

Another theory of Thompson’s was that Mayan glyphs had no phonetic element to them and that they only represented complete ideas. This theory was disproved after his death, like many of Thompson’s other theories which were based on his own misinterpretations of Mayan glyphs. Even so, for many years most archaeologists and writers accepted Thompson’s and Lothrop’s theories as facts and began to repeat them in their own books and reports. In 1970, Thompson published a popular book, Maya History and Religion. The book was translated into Spanish and sold like hotcakes. In the book, his old theory was presented as fact. From that moment on and with the help of dozens of writers including American and Mexican archaeologists once again using modern texts like Thompson’s and Lothrop’s as their sources instead of the original historical texts, Ix Chel would be linked firmly in the collective memory with a pilgrimage to a temple erected for her in Cozumel.

The Truth In Print About Ix Chel

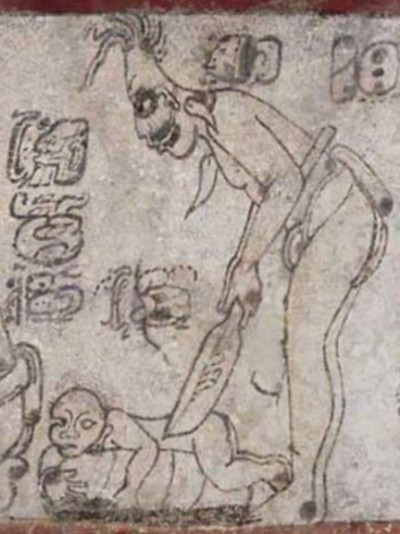

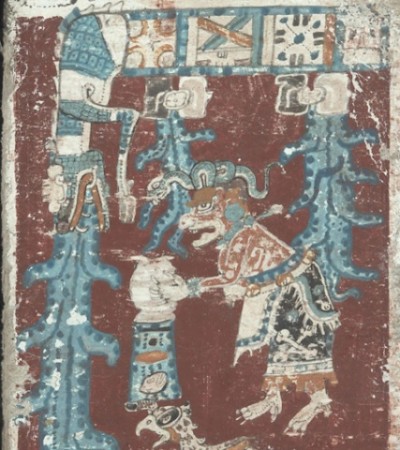

But what do the original texts say about Ix Chel? In truth, not much. There are only a meager hand-full of mentions of the goddess in the early records and many of them contradict one another. An image of a goddess whom archaeologists call “Goddess O” that appears in the Dresden Codex is identified as Chac Chel (Red Chel) by the portrait-style name glyph prefixed with the chac, or “red” glyph placed close to her image. She is also identified in the same codex as Chac Che (Red Che) with compound phonetic name glyphs which also appear next to her. In the Madrid Codex, the aged goddess “O” is named variously Chac-Chel-Chac and Ix-Kab’-Chel in compound phonetic name glyphs. She is also depicted in that codex sitting at a loom weaving and wearing spindles in her hair, and from that (along with her association with spiders in the Ritual of Bacabs manuscript), she is assumed to be the goddess whom the Maya believed introduced weaving to the world.

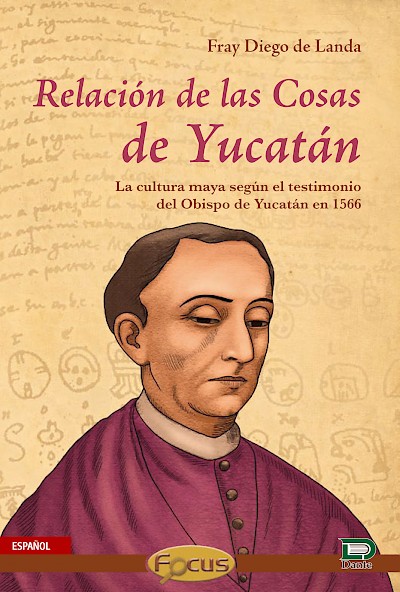

Ix Chel’s name appears in a simple list of goddesses in the abstract of Bishop Diego de Landa’s now-lost 1566 manuscript Relación de las cosas de Yucatán: “...the gods of that land such as Aixchel [Ix Chel], Ixchebeliax [Ixchebelyax], Ixbunie, and Ixbunieta…” The earliest Mayan language document in which the goddess’s name appears is the 1612 document written by the cacique of Acalan-Tixchel in southern Campeche, Pablo Paxbolon, in the Chontal Mayan language. That document simply lists “Yschel” as one of the many different idols found in all the Chontal villages, and nothing more. The next earliest Mayan mention of the name Ix Chel is in the post-1779 Ritual of the Bacabs, a Yucatec Mayan language manuscript that is a collection of ritual incantations. In the manuscript, both red and white Ix Chels are mentioned in several places, as well as yellow and black Ix Chels and an association of the goddess with spiders. Just like the Bacabs, the various Ix Chels took their color names from the cardinal directions they represented. None of these texts say anything about a relationship between the goddess and Cozumel, a women’s pilgrimage to her temple, or fertility.

Bartolomé Investigates Too

Bartolomé de Las Casas (who never set foot in Yucatán) weighed in with some information about the goddesses Ix Chel and Ixchebelyax. In correspondence with fellow cleric Francisco Hernández (who was living in Campeche), Las Casas asked Hernández to use his Mayan linguistic skills to interview someone who might be able to tell them something about the Maya gods. Hernández wrote back a year later that he had found a Maya elder (presumably in Campeche) and interviewed him. The results of the interview were recorded in Las Casas’ document Apologética historia sumaria de las Indias Occidentales, written during the period between 1527 and 1559. In his manuscript, Las Casas states that the Maya believed “God was the Father and Son and Holy Spirit. And that the Father was called Izona [Itzamna], who had created mankind and all things; the Son had for his name Bacab, he who was born of a young woman who was forever a virgin named Chibirias [Ixchebelyax], who is in the heavens with God, and the mother of Chibirias is called Hischen [Ix Chel].”

This contorted description of the Maya gods sounds incredibly like a Mayanized version of the Christian dogma regarding the Holy Trinity, Saint Anne and the Virgin Mary that Hernandez’ informant created in an effort to legitimize the Maya beliefs in the eyes of the church. In the same document, Las Casas later reverses the roles of Ix Chel and Ixchebelyax and says that Ix Chel was the wife of Itzamna and not his daughter: “…in the beginning there was no heavens no earth, no sun, no moon, no stars. There then was a divine couple, who were called Xchel and Xtcamna. They became mother and father, who engendered thirteen children, and the oldest, with some others with him, thought of themselves better than they were and wanted to create creatures against the will of their father and mother, but they couldn’t...” López de Cogolludo in his Historia de Yucatán (written around 1655 and published in 1688), says: “the mother of Chiribias [Ixchebelyax] is called Yxchel.”

Goddess of Medicine?

Landa also explains that Ix Chel is the goddess of childbirth and medicine, although he points out in the same sentence that the Maya had at least three other gods of medicine and then names them. Cogolludo likewise states that Ix Chel was the goddess of medicine, but just like Landa, he too points out the Maya had other gods that did the same thing. One must note, however, that absolutely nowhere in these early documents is Ix Chel described as the goddess of fertility. She is only described as being related to medicine and the act of birth. This is not surprising, as all of the early Mesoamerican cultures had a goddess who was the patroness of childbirth, an act that these cultures viewed as something akin to a battle and not the blessed, wished-for event that we consider it today.

In Conclusion

So what does this all mean? It means that there is no evidence or testimony in the first four hundred years of documents of the history of Cozumel that there was ever a women’s pilgrimage to a temple dedicated to Ix Chel on Cozumel and that there is likewise no historical document or text associating Ix Chel with fertility. Both of these ideas originated in the twentieth century and have been embraced whole-heartedly by travel guide writers, tourist boards, and website authors. But, will this article or the book convince people to abandon their old beliefs regarding the goddess Ix Chel? How about the idea that Jacques Cousteau is the man responsible for popularizing diving off the coast of Cozumel?

Probably not. As the saying goes, “it is easier to fool people than it is to convince them that they have been fooled.”

Comments

Leslie 10 years ago

As a grad student in archaeology (PhD) who will hopefully soon be working on Cozumel, I would be very interested in speaking with you! :]

Reply

Ric Hajovsky 10 years ago

Wikipedia is the bane of my life! It has led so many people astray it is unbelievable. At one time I tried to correct and update sections of material on Wikipedia that I was extremely familiar with and had spent years researching, only to see it replaced with old wives’ tales a few hours later. It was like trying to plug the dike with my ten fingers; every time I plugged one leak, another sprang up nearby. I finally gave up. A few of my updates remain, but they are dwindling by the month, as I no longer repost them after someone replaces them with something they heard from a tour guide.

Wikipedia caters to the person who just wants an answer, any answer, without needing to apply any amount of critical thinking on the results. I imagine some of its pages reflect the truth, but it is only the roll of the dice whether you land on one of these pages or not, because, as you say, anyone can post anything on any Wikipedia page, or take anything down, for that matter.

They also have a ban on original research. That means, if an old theory or common belief is disproved by new research, Wikipedia will disallow the new research in favor of the old, outdated material. I assume that is done to prevent individuals from posting unsubstantiated original theories or ideas, but it has the results of suppressing substantiated new discoveries. Instead, Wikipedia gives preferential treatment to well-worn old saws or conventional wisdom.

Reply

Colm fiftyfour 10 years ago

All very interesting reading. However most folk will use Wikipedia as a reference. Fortunately you can edit it to perhaps correct future errors.

Reply

Ric Hajovsky 10 years ago

Thanks for your comment, Salvador!

Besides the lines you quoted from Jean-Michel's blog, he also wrote in it "Bravo developed a fascination for sharks and devoted a large portion of his life to filming and studying sharks. He is widely known for the discovery, study and photography of 'sleeping sharks' near Isla Mujeres in the Caribbean in the 1970s."

Wikipedia and at least 19 other websites now repeat this statement appearing in Jean-Michel's blog word-for-word. That is how misstatements become "history."

I knew Ramon Bravo and do not mean to detract from his legacy when I say that the claims that he was the discoverer of the sleeping sharks is a myth. Even Bravo himself admitted that it was his friend, Carlos Garcia Castilla (a.k.a. "Valvula"), who told him about the sharks and who led Bravo to them for the first time in 1969.

As far as the suggestion that Jacques Yves Cousteau's interest in Bravo's work on the sleeping sharks was the source of the legend that says Cousteau put Cozumel on the map via a 1960 documentary, that does not fit with the historical time-line, since there are references to this legend that were in print prior to Bravo's first sighting of the sharks in 1969 and Cousteau's own 1974 film "the Sleeping Sharks of Yucatan," in which Bravo appeared and was aired as an episode on "The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau." I will agree with you, though, that many people mistakenly believe that this sleeping shark episode was aired many years earlier than it actually was. I have seen many authors incorrectly state that it was shown on TV back in the 1960s. Though the series ran from 1968 through 1976, the episode on Bravo's sharks didn't air until 1974.

Ric

Reply

Salvador Puente 10 years ago

this is anote from the page http://www.oceanfutures.org/news/blog/ramon-bravo-mexican-diving-legend

"Around the same time as my father, Jacques Cousteau, was donning his newly co-invented SCUBA gear and traveling the seas aboard Calypso with his team, there was also a famous Mexican diver, photographer and filmmaker by the name of Ramón Bravo who was exploring the undersea world – bringing the beauty of the ocean world to Mexico, the Americas, and Europe through his numerous underwater films, photography, and books. He is known as the most beloved diver of Mexico"

Cousteau was fascinated with some films made by Ramon Bravo about sleeping sharks. This is the source of the "legend". Check the site

Reply

(0 to 5 comments)