One Last Effort: Intro and Chapter One

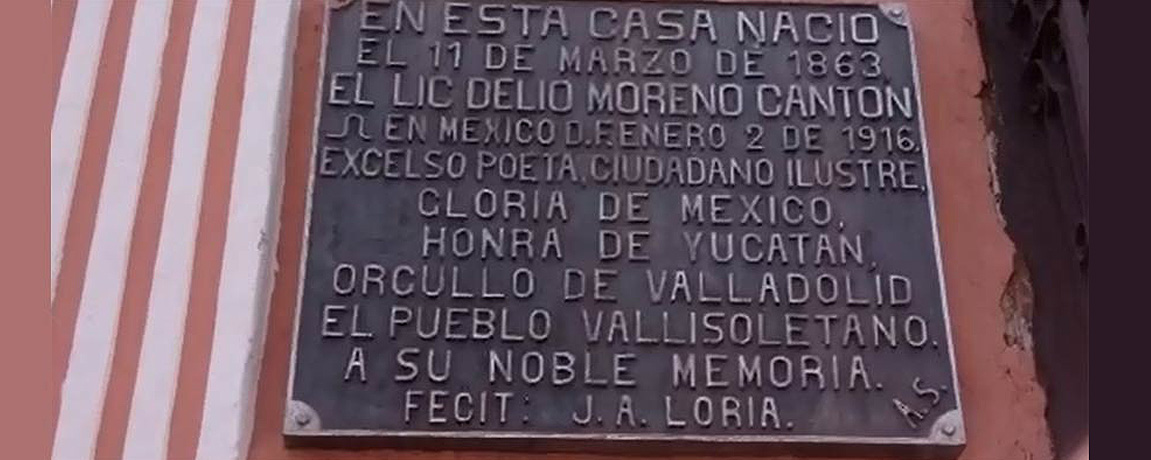

Editor's Rather Lengthy Introductory Note: After seeing a plaque in Valladolid marking the birthplace of Delio Moreno Canton, Nadine Calder began reading about this journalist, poet, novelist, playwright. While some of his poems had been translated into English, to the best of her knowledge, his two novels set in Merida had not. Neither Nadine nor this editor imagine that either of these novels would have a large audience nowadays. They represent the time in which they were written, at least as much as the place, so most contemporary readers may find the stories overly sentimental. The fact that they offer a glimpse of old Merida is the reason that Nadine was interested in translating Canton's works, and the reason that we are interested in publishing them here for our readers.

Nadine Calder was a college English teacher, and her undergraduate degree was in Spanish. She has studied in Mexico, and therefore has some background in Spanish and Mexican literature. The translation was painstakingly slow and aided by multiple references, including Spanish-teacher friends in California.

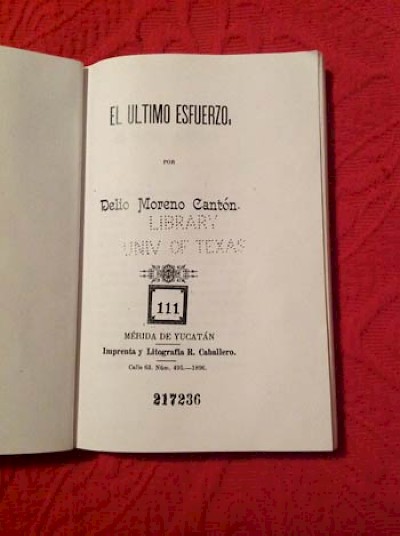

What follows is the first chapter of the translation of Moreno Canton's earlier novel, El Ultimo Esfuerzo (One Last Effort). Written in the third person, the story includes a variety of characters, situations, and street scenes (for example, one prominent señora takes every opportunity to mention that her home features a zaguan). A second edition was published in 1947 by the University of Yucatan, whose library made a copy for Nadine so that she could make the translation. As far as we can determine, the novel is unavailable for sale, even in Spanish. A public-domain copy of the 1896 original is on Google books, and it is available free online. If, like Nadine, you want a bound copy, you can place an order for one with the Harvard Bookstore rather than print it out yourself. Moreno Canton died in 1916, so it is our understanding that there are no copyright issues. In deference and out of respect for Nadine's hard work, we request that these translations not be reproduced from these pages without Nadine's permission.

So here begins our experiment. We will publish one chapter per week here in Yucatan Living, until the entire book is published on our website. We hope that our readers who are interested in the history of Merida and its literature will enjoy the fruits of Nadine's hard work.

****

The Author

Delio Moreno Cantón was born in Valladolid, Yucatán on March 11,1863. He attended school there until the age of fourteen, when he was sent to Mérida to enroll in the Catholic High School of San Ildefonso, where the Hotel Caribe is now located. He would go on to study law while writing poetry and beginning a career in journalism. He eventually wrote a thesis arguing in favor of the legalization of divorce, which was then indissoluble in Yucatán. He became a lawyer in 1890 and participated in politics, continuing to write poetry, novels, and plays. He unsuccessfully ran for governor of Yucatán as a progressive reformer in 1909 and 1911 and he died in Mexico City in 1916.

Introduction to One Last Effort

Moreno Cantón’s academic, literary, social, and political backgrounds merge in his first novel, One Last Effort (El Último Esfuerzo), which was published in 1896. An introduction to the book’s second edition in 1947 calls it an “enchanting amusement, brimming with Yucatecan, rather Meridano, humor.” It goes on to describe the book’s quixotic bachelor, don Hermenegildo López, as “a fully realized character, almost a portrait” of a type still walking the streets of Mérida half a century later.

Other characters caught up in the mischief, gossip, and ambiguities of love and marriage include doña Raimunda, the neighborhood’s self-appointed social director, doña Prudencia, widow of a plantation owner, and her daughter Lupita, and the young men vying for Lupita’s affections. There are lavish preparations for the celebration of doña Raimunda’s saint’s day and the intrigues of a political campaign. There are hopes, ambitions, and disappointments. Treating his characters with humor and affection, Moreno Cantón’s vocabulary is carefully chosen and his sentences complex as he attempts to convey the intricacies of human behavior that he so precisely observed in Merida many years ago and preserved so we could read about them today.

We hope you enjoy this window back to another time in Merida!

****

El Último Esfuerzo: Chapter One

The street is neither narrow nor wide. It can't be said to be in the center of the city but neither is it on the outskirts. Some people who live on it enjoy some degree of social standing and as there’s no shortage of young women who, in addition to being young, are beautiful, it is free of the air of desertion that reigns on many other streets since, from the early evening hours, it is visited with considerable frequency by suitors. Several are the doors that open then, allowing the houses' interior light to pass into the street, and it is not unusual to hear the sound of a piano with which an enthusiastic student tries the patience of the neighbors.

The house of Señor Licenciado Felipe Ramos Alonzo is similar to the street: neither good nor bad. Its design is that of a zaguán, the wide central hallway that leads from double front doors all the way through to the patio, a feature much to the liking of his wife, who takes care to mention it whenever the opportunity presents itself; but the house isn't especially graceful, with few bedrooms in addition to the parlor which, although not much different from the other rooms, boasts yellow-colored walls painted with white rosettes. The licenciado would have had wallpaper installed, but upon hearing what it would cost, he decided that it was too great a luxury for the current times, and his doña Raimunda agreed with him, even venturing the opinion that paint is better and more elegant.

The chairs were unremarkable, but the mirror, oh! The mirror was undeniably the best in the neighborhood; and it could not have been otherwise, because as the señora firmly maintained, it had cost one hundred and fifty pesos, and to a cousin of hers, she even once claimed more than two hundred.

Not many more months would pass before a piano, on a par with the mirror, would arrive to complete the furnishings, when Felipito, already twelve years old, would complete the music theory class he was studying at school upon his father's recommendation and his solicitous mother's insistence.

Facing the mirror, covered with gauze to protect it from fly specks, was the seating area, carpeted and composed of two pairs of rocking chairs and a sofa; but usually the only people received there were those of some importance or with whom the family was not well acquainted, as ordinarily, friendly visits took place in the doorway, spilling out onto the sidewalk to the extent that during the rainy season, passersby bad-mouthed the poor upbringing of those who thereby obliged them to step down into the muddy gutter.

As the licenciado was usually out, doña Raimunda's visitors were doña Prudencia, widow of a plantation owner, at times her daughter Guadalupe, one or another of the remaining neighbors, principally married women, and almost always, don Hermenegildo López, a character in his fifties, given to complaining about his misfortunes but the model of courtliness.

It was rare, upon the bells' ringing the angelus, that good old don Hermenegildo would not show up at the end of the street in search of his seat at the traditional gathering at the house of Señor Licenciado Felipe Ramos Alonzo. It seems I can still see him coming with his tall stature, his step careful and measured, leaning on a gnarled walking stick.

Upon arriving at the doors, already wide open——although before early evening only one of the zaguán's doors stood open——he would knock lightly to announce himself, and then entering the parlor, inquire in detail about the family, if Felipito's health continued to be good, and about everything else that could possibly show his attentiveness. Then putting down his hat, he would take a chair and go out to seat himself irreproachably in it, without ever crossing his legs or striking a pose for which he might be accused of abandoning or forgetting the most exquisite of social graces. There he would remain until doña Raimunda should come out or one of his fellow visitors show up, his scant tuft of hair exposed to the elements, frequently killing time by smoking his holoch cigarettes, rolled in corn husk, the only ones he liked, to satisfy his modest taste for tobacco; but that did not mean he would not accept, always if it were offered, one rolled in paper or a cigar, which regularly received his praises in grateful compensation for the gift.

His suit was his everyday suit, a garment of venerable antiquity that in every one of its parts showed the faithfulness and prolonged service they had given their owner. Pants that must have once been dark-colored, threadbare and frayed on their lower edges from rubbing against his shoes, and with big, thick patches on the seat. In truth the latter could not be seen unless don Hermenegildo bent over, as ordinarily they were hidden by the tails of his frock coat, no less honorable for its age, olive-colored today but black in its better times. Such a condition would not have befallen it, however, nor its accompanying vest and pants, due to the indifference of the appreciative owner as it was essential that he, before going out, give all of them a good brushing to get rid of any stains and dust, robbing them of the already scant nap that remained on them.

This is not to say that the situation had come to the point that don Hermenegildo’s trunk would have remained empty with the absence of the suit the good gentleman habitually wore. He had one other that he conserved like gold dust for grand occasions and that was not very new, but it was certainly the best that he had. The frock coat was a bit out of style and the buttons placed at the base of the tails were different from those in front because it was not possible to find identical replacements when the originals were lost. But in any case, with the better suit or the other one, he went down the street magnanimously, bowing ceremoniously to greet everyone, an action always accompanied by uncovering his head with the subtle gesture of his tipping his hat to the person to whom the greeting was directed, earning him points for his respectability and no little credit as a courteous man.

And for good reason. He had been born unlucky relative to other matters. He was left defenseless upon the death of his father just when he was going to begin the study of Latin in the seminary in order to later acquire the title of lawyer, which would have given him an honorable profession in the arts. And he was now living in poverty, suffering from extreme scarcity which his meager salary as a court clerk could not relieve, but...

"I can't complain," he used to say to a certain friend to whom he repeated the same thing for the hundredth time. "You are my witness that I have nothing, that my luck couldn't be worse, still, everyone loves me; believe me, I know what I’m talking about."

And he spoke of his rewarding friendships and of the attentions they showered on him. When they saw him arrive at the house of señor so-and-so, the wife would ask him about his health. If it was the dinner hour, the daughters would together insist that he take part in the meal. In the home of señor someone-or-other, it was worse. Whenever they saw him pass by, they would call out, sweetly reproaching him for the fact that it had been two days since they had seen him. What! If in the most distinguished houses, the señor, the señora and the children all went completely out of their way for don Hermenegildo when he walked by, it is that they know very well that while he may be without resources, for his part he gives his all for each one of those persons.

"That's why you see that when something has to do with señor so-and-so, there is Hermenegildo López as the one who most... well he is among gentlemen the grateful one. Believe me, I know what I’m talking about."

****

Continue reading with Chapter Two of El Último Esfuerzo!

For those who like to follow along in Spanish, you can find the Spanish version on Google in Google Books here.

Comments

James Gunn 10 years ago

I've been meaning to write to congratulate and thank you for the effort to make this translation of Delio Moreno Canton. He seems to be following in the tradition of the "literature of manners" that was very popular in Spain in the late 1800s. Ramón Mesoneros Romano was one of the best known of the Spanish writers who popularized this style.

I am now reading your translation for the second time. I appreciate the hard work. I've done a few translations myself, so I know how difficult it can be.

Cheers,

James Gunn

Reply

(0 to 1 comments)