One Last Effort: Chapter Eleven

Home Life

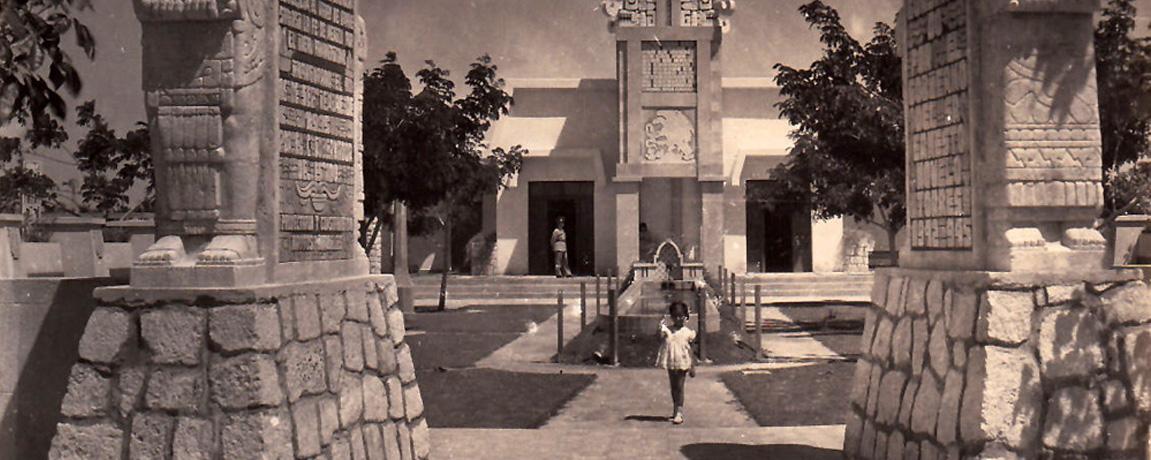

It seemed impossible that so many people and so much junk could fit into the two holes in the wall where the bachelor’s sister lived with him and her seven children. In one of them, with smoke-darkened ceiling and grime-coated walls, there was a large table wrapped with sheets that was used for ironing, which was the industry with which his sister Teresa helped don Hermenegildo with the household expenses.

On the hooks in the wall could be seen the rolled hammocks, and in two of the corners, at hand height, ropes were extended to show off, like the best coat racks, a jumble of dirty clothes in which it was as likely to see a petticoat as a pair of little boy’s pants, full of tears and patches. On the floor were pots and pans, when they weren’t being used in the kitchen, alongside crates on which were some beat-up trunks; for their part, these held the big baskets for the ironed clothing, and other odds and ends for domestic use appeared elsewhere.

At night, with the table shoved up against the wall, that tiny room was converted into a dormitory for the señora and five of her children, four who slept two by two and one, the youngest, beside her in the hammock which was biggest, or to put it more accurately, least small.

The other room was assigned to don Hermenegildo and his two older nephews, who also slept together; because while sleeping in that house, the fifty-year-old was the only one who comfortably stretched out his shanks without danger of coming up against the obstruction of another body, even though there was little certainty that his legs wouldn’t end up outside the narrow hammock, which had little of itself to offer.

At best, from what could be seen, that room was the place to receive visitors, with five somewhat rickety chairs and a padded rocker which was missing an arm, leaving in its place only the tip of a screw that served to snag any clothing that came into contact with it.

A table that could be used for writing, a trunk less damaged than the others, and an old shelf that had lost the color of its paint fit laboriously into that hovel, theater of don Hermenegildo’s musings and of the vigils that made him suffer his younger nephews’ cries which thus intensified the aches and pains of his lamentable life.

This changed somewhat with the death of doña Prudencia, as it served to interrupt his promising dreams of matrimony’s good fortunes.

Hermenegildo’s Dilemma

The fifty-year-old was wondering if he should observe mourning for the widow’s death, and after much hesitation, he finally decided to place some inconspicuous crepe next to his hatband and to pass the hours in sadness as a sign of his profound pain.

He imagined that he had suffered a loss that wounded him deeply, and it is certain that, had he known of those things, he would have compared his luck to that of Dante upon his loss of Beatrice. However, doña Prudencia’s remains could sleep in peace, sure that they had not, with a spark of love, removed the clerk’s dry heart.

He skipped doña Raimunda’s gathering those first days, but his return was fertile ground for jeremiads on the loss that he had suffered, and to which he referred while greatly arching his eyebrows and giving his eyes an expression that made them seem to contemplate from his gaunt face the stingy tomb that guarded forever the object of his newly truncated illusions.

Aside from his love for the deceased, his past loves, if they could be called that, didn’t occur to doña Raimunda and the lawyer. Don Hermenegildo’s lack of ardor and great reserve weren’t conducive to getting to know him, and the licenciado don Felipe Ramos Alonzo’s spouse only remembered the bachelor’s loves when she had him in front of her to get him to talk and make her laugh for a while. Lupita didn’t have the slightest suspicion that don Hermenegildo’s visits had any but the ordinary objective and so, although he would have liked the whole world to pity him for the great misfortune he had undergone, he frequently sighed without having anyone stopping to think about it.

Making The Best Of Bad Luck

Convinced that the adverse star that pursued him was depriving him of the conjugal state just as he felt inclined to embrace it, he resolved to make his sister Teresa’s family more his own and to see his nephews as compensation for the children that heaven was denying him.

He dedicated himself to their care and made the eldest, Lucas, study daily, reviewing his lessons before sending him off to class at a free school. The second was barely seven years old, and don Hermenegildo decided to get him started on the challenges of learning the primary subjects in order to avoid the drawbacks of sending him to school, not the least of which was the necessity of providing him with clothes; at home he could easily go around shabby and dirty, as always, eventually converting to shreds his older brother’s already-unusable rags.

The latter, aside from being an incorrigible prankster, for which he suffered frequent detentions in school and tugs on his ears at home, seemed intelligent and was benefiting from his lessons. His books could have been handed down to his little brother, but when he was finished with them, only the last pages were left and those had come unstitched.

Evil Genius

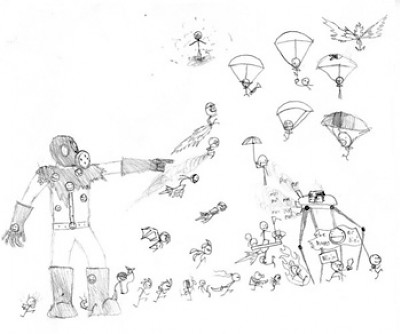

Ramoncito, don Hermenegildo’s primary-student disciple, wasn’t any more careful. After two weeks he had already defaced nearly half of a paperback copy of the primary book by Mantilla, and everywhere on the pages, despite his teacher and uncle’s warnings and threats, could be seen numerous strokes and extravagant figures done in pencil, a sign of the child’s early love of drawing. The pencil had come from a rascal in the neighborhood, a buddy of his, in exchange for a good amount of tamarind seed, currency used in the games of hoyuelo* and arrimadilla**.

What Ramoncito shone at was drawing people. Any paper he found, and walls alike, served him as canvas for his artistic conceptions. Those soldiers in the making were his delight, and he showed them to his friends with pride.

He would draw a circle destined to be a head, and inside he would put a pair of points to represent the eyes; from each of the places where the ears should be, he drew a horizontal line in the guise of an arm, which ended in another five, opening like a fan to represent the fingers; downward, in place of the neck, he drew two parallel lines which fancied themselves legs, and there you have a quintessential man.

Later converting this individual into a troop was for Ramoncito a simpler procedure than that employed by the government. He crossed that phenomenal body with a line that stuck out to one side of its head, and its rifle was at the ready; a dozen figures like this and a company was formed.

Don Hermenegildo needed a good dose of patience to see to it that this precocious rival of Apelles could overcome the difficulties of spelling, and he had to think about teaching him the multiplication table. All this in those moments when he found himself free of his commitments as clerk and his customary attendance at his excellent friend señor licenciado don Felipe Ramos Alonzo’s traditional gathering, which he had missed only once in order to visit Lupita.

And so two more years of his life went by, amid the pressures of domestic life, the whining of his little nephews, and the arguments brought on by the older ones. And so he would have continued to live with the same prosaic monotony if life, which has so many ups and downs, didn’t have in each one of them varied and new developments that change the face of things and shoot down man’s hopes and expectations.

****

*”dimple:” A child’s game in which, throwing from a distance, one tries to land coins or pellets in a hole.

**”come close:” A child’s game in which each player tosses a marker (coin, button, etc.) against a wall attempting to have it remain as close as possible to the wall; the one who succeeds in landing closest wins all the markers.