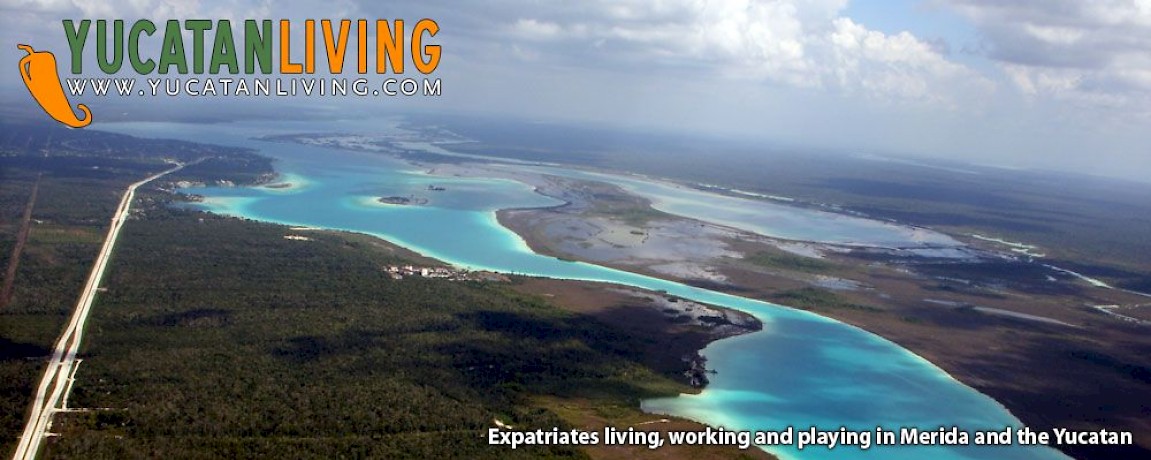

Laguna Bacalar Flyover

We don't get out to the right coast of the Yucatán as much as we'd like to, so we're always happy to hear from our friends who live and work there when there is something interesting going on. Scott Wallace, who lives in (on?) Laguna Bacalar, sent us this story recently which we would like to share with our readers. Scott writes about his experience with scientists from Austria doing a geological survey of the fresh water underground aquifers on the east side of the Peninsula. Fresh water has always been pleasantly abundant underneath the Yucatán Peninsula... in most parts of the peninsula, if you can drill 60-70 feet down, you can have a fresh water well, just like we do in our backyard. The last ten years of breakneck development, especially along the Mayan Riviera, have made the understanding of how much water there is and how it flows vital to the future of sustainable tourism in the Yucatán. We were thrilled to read this story and to learn that something is being done and there are people being proactive about this issue.

>

Scott and and his wife and business partner Peggy Londahl have lived in Bacalar for six years now, running a web business in the Laguna Bacalar area. Scott had the privilege of traveling with the project team from the Amigos de Sian Ka’an non-profit and the Austrian Geological Survey as they took to the sky to discover what lay underneath the ground, and he shares his story with us...

Once In a Lifetime...

It's a March morning and Laguna Bacalar presents an impressive vista as we fly two hundred meters over the lake in an aging Russian cargo helicopter which now serves as part of the Mexican Navy’s rescue and emergency fleet. The rear of the helicopter has been removed and a series of instruments are mounted there, pointing at the ground below and capturing video, altitude, and temperature. Other instruments measure gamma radiation, magnetic field strengths, and extremely accurate GPS readings. Most important of all, dangling sixty meters below us from a large opening in the floor is a six-meter-long Geotech Hummingbird (significantly customized and referred to as “the drone”) that gathers data about the water, minerals and other aspects of the earth below.

The view of the lake and jungle is captivating, providing cognitive dissonance with the noise inside the helicopter, which is deafening. On the other side of the opening in the floor Martin Heidovistch, wearing earplugs and a headset, leans over his keyboard and points at the flat-screen monitor. The monitor displays the numerous instrument feeds from the sensors and equipment on the helicopter. As tech support staff for the Geological Survey of Austria, Martin has much experience at this and he doesn’t say a word, but instead scribbles a query on his notepad. He quickly shows it to Ingrid Schattauer, a GSA geologist, who then leans forward to look first at her hand-held display, and then at the data streaming across the screen. Then she writes her reply on the same notepad. Martin speaks through his headset to the pilot, a minor course adjustment is made, and Martin goes back to tabbing from data window to data window, scanning for anomalies that require instrument or flight path adjustment.

Below Martin, and also on the screen in a video window in front of him, the drone ghosts through the air in an awkward slow-motion dance led in part by wind shifts and in part by course adjustments. The drone housing holds an industrial PC, a digital GPS, a digital magnetometer, and the transmitters and sensors for capturing the earth’s resistivity. “Resistivity” is a measure of a substance’s ability to inhibit the transfer of electrons; more or less the opposite of conductivity. The resistivity of the earth is measured in a cone that is directly below the drone sensors and approximately 100 meters in diameter on the ground, decreasing to about 30 meters at the depth the signal dissipates. Properly captured and processed, resistivity shows in great detail the makeup of the earth from its surface to about 100 meters deep.

Resistivity data is difficult to turn into accurate geological maps because many things can interfere with data collection. All the resistivity data captured during this and other flights must be reviewed in the context of the other simultaneously-captured data streams. For instance, if the altimeter indicates that a set of resistivity readings were made greater than the ideal 100-meter height, then adjustments must be made to the affected data. If the GPS indicates that the velocity is 107 kph rather than 100, adjustments must be made to the collected data. Magnetic variances in the earth can also affect the data, as can variances in background gamma radiation. Each moment’s resistivity data must be assessed in terms of these other data streams to determine if, and how, to adjust the collected resistivity data.

How Did I Get Here?

The drone collecting the data is a light (100 kilos), narrow (30 cm in diameter and 5.5 meters long), durable plastic tube with stabilizing fins on the rear and a domed front, suspended by a braided nylon cord. The cord is attached to the helicopter chassis by four one-inch steel cargo-cables connecting to a one-ton break-away clasp designed to prevent anything that might be snared below from bringing down the chopper. Two A/C lines that power the equipment and a LAN cable are all wrapped to the cord and these tether the drone to the upside data collection PC and storage array. At the rear of the helicopter are mounted a large metal box that measures gamma radiation, a video camera pointing directly down, a digital laser altimeter, and another digital GPS.

Before the flight, all of this equipment – and the equipment in the drone – had to be mounted to the aircraft, connected to various power supplies, coupled to the data collection interfaces and PCs and then tested and calibrated. Dr. Andreas Ahl, a geophysicist from GSA, directed the calibration efforts as Ingrid and Martin went through the routine but complex procedures. Preparation was time-consuming and during the last half of the process the Navy airmen readied the helicopter. When the GSA team was ready, the pilot and staff completed their pre-flight checks and the chopper was fired up.

Into The Blue Again

As the chopper lifted off, we were sitting a meter or two away from the turbine and rotors and there was an immediately deafening and increasingly louder racket. I noticed then that everyone else was wearing ear protectors and quickly grabbed a spare pair dangling from a cargo cable and clamped them onto my head. The lift off was done carefully. Despite that, because of gusting winds, the helicopter moved around a bit left, right, forward, and aft. The drone rested on the ground twenty meters away from the helicopter in a cradle and as the chopper rose very, very slowly, a team of Navy personnel stabilized the drone and paid out the nylon cord with the power and LAN cables, making sure that the air turbulence didn’t snarl any lines. An airman aboard the helicopter carefully held the cable bundle and watched the liftoff through the floor. Talking constantly to the pilot, the airman advised him of the cable location and directed any adjustments in ascent, orientation, or direction. After about ten minutes, everything was in good order and we were up about 100 meters, looking out over the city of Chetumal with the Bay of Chetumal, the Belize coast, and the Caribbean beyond.

The four Navy staff relaxed a bit while the pilot headed toward Laguna Bacalar and beyond. One of the airmen opened my porthole and I peered out of the helicopter, down at the highways and neighborhoods where I live, but had only previously seen at ground level. Soon we were far away from civilization and heading out over low selva (forest) and wetlands toward Laguna Bacalar.

Same As It Ever Was

Located in the nearly flat southeastern corner of the Yucatán Peninsula, Laguna Bacalar is an extraordinarily beautiful lake and the second-largest freshwater lake in México. Almost fifty kilometers long and crystal clear, the lake varies between one and 25 meters in depth and is fed by several mineral-rich submarine cenotes and a few small rivers which flow from nearby jungle cenotes. Meandering marshes and wetlands, rich with birds and other wildlife, border the lake on three shores. Archaeological studies indicate that Laguna Bacalar's beauty and tranquility has drawn visitors for well over 2000 years. Sometime about ten thousand years ago, a seismic upheaval lifted one shore of the lake nearly 50 meters, creating a fault-escarpment on the west and a tsunami of saskab silt, now covered in mangroves, that still defines the area for many kilometers to the east of the lake. Shortly thereafter, Maya settlements were established with homes situated on raised earthen platforms and for centuries before Europeans arrived, Bacalar was a key Mayan port and trading center.

The town today lies at one of the shore’s highest points, directly overlooking the lake and the river that gives access from the Bay of Chetumal. For more or less the entirety of the Pre-Classic and the Classic Maya eras (from 250 BC to 1540 AD when conquistadors took the city), Bacalar and Laguna Bacalar were important parts of Maya life in the Yucatán. Bacalar was an administrative center and port in the Maya province of Uyamil, one of sixteen city-states in the governance structure of the Mayan Yucatán peninsula. The lake and nearby cenotes provided unlimited fresh water for the population. Honey, fish, agricultural products as well as critical transportation and trading services characterized the commerce between Bacalar and other Mayan centers to the south in Honduras and Guatemala.

Letting The Days Go By

On today’s trip, we fly over the lake just south of the town of Bacalar. The goal is to scan an area 45 kilometers northwest of Laguna Bacalar along a known geological fault that holds the promise of underground water. Basically, we are going to go back and forth across the target area in a pattern of parallel passes. To maintain the integrity of the data gathering, the drone must travel at 100 kph, 100 meters above the ground in a straight path that is parallel to and 100 meters distant from the previous pass. Given the considerable variation in wind speed today and the fact that the terrain includes hills and valleys, this is a challenging task for the helicopter pilot. The team will scan an area of approximately ten square kilometers, taking about 45 minutes. We will be in the air just under three deafening hours, most of that time in transit.

During each of the scanning passes, the aircraft moves steadily and we can see the green jungle out the rear of the helicopter. At this altitude, individual trees, openings in the forest, small cenotes, palapa-roofed Maya family settlements, dirt tracks and game trails are all clearly visible. At some point in each pass, the pilot banks the helicopter into a 180 degree turn that clearly signals the pilot has completed this pass across the target area and is preparing for the next.

Water Flowing Underground

The helicopter and airmen are provided by the Mexican Navy to support this fresh water aquifer-mapping project, believed to be the first of its kind in the world. An ambitious collaboration between the Geological Survey of Austria and the Amigos de Sian Ka’an (a non-profit dedicated to preservation of the Sian Ka’an biosphere preserve), this several-year effort will trace and analyze the underground aquifers of the Yucatán Peninsula, the world’s largest karst field and possibly the largest underground freshwater reservoir on the planet. Karst is carbonate rock (formed when seismic disturbances lifted immense, flat coral reefs and left them high and dry forming the Yucatán Peninsula) that has been eroded by acidic rainfall or runoff to create sink-holes and sub-surface caves. These underground chambers and faults enlarged over time to become, in this case, a significant, interconnected subterranean river and aquifer system. Several years ago, to confirm the applicability of Geological Survey of Austria’s aerial scanning to the Yucatan’s geology, Amigo’s de Sian Ka’an and GSA made initial tests in the Tulum area where scuba divers have over decades carefully mapped a number of underground rivers. After the fly-over scans of the area that the divers had mapped, the very large data set was taken back to Austria where it was pre-processed to minimize interference and maximize accuracy. The validated data was then analyzed and presented in numerical and graphical format. The results were surprisingly accurate and useful. Not only was every single known underground system detected and modeled correctly, a number of systems unknown to the divers but within the same scan area were detected. The divers subsequently explored those and validated their existence and that their configuration was consistent with the GSA and Amigos models.

The data captured during this year’s aerial surveys is now back in Austria with Martin, Ingrid and Dr. Ahl, where the lengthy processing and merging of the data sets is underway. The Navy helicopter and crew are back on regular duty. The Amigos de Sian Ka’an organization is waiting for the survey results so their scientists and staff can prepare a regional map of water resources. With an accurate, detailed vision of the entire region in hand, Amigos de Sian Ka’an can coordinate with public entities and others to develop strategies and programs to protect strategic fresh water and prevent negative environmental impact on important ecological resources. Despite the time and expense undertaken so far, only a small fraction of the Yucatán Peninsula has been scanned, even including the datasets just returned to Austria.

Government programs and private industry plan enormous expansions of tourism south from Cancun and Tulum down towards Bacalar. Informed management of these fresh water resources – and of historically poorly-managed waste water – are vitally important to protecting these aquifers and providing a foundation for sustainable growth. In several months, analysis of the new data will be complete and the results will be available.

After The Money's Gone

It’s hard to overestimate the value of this research for the management of freshwater and wastewater and for guiding inevitable growth in tourism and urban space. Preliminary findings from earlier flyovers and from reviews of conventional geological analysis confirm the Bacalar area’s importance as a key freshwater ecosystem. This large ecosystem is important not only for southern Quintana Roo but for the Yucatán aquifers far to the north and for the urban developments and tourism that draw upon those aquifers. And so it is with a curious technological twist that Bacalar and its beautiful Laguna de Siete Colores (Lake of Seven Colors) still maintain – even after several millennia – a critical life-support role for the Maya of the Yucatán and those who come to live in their land.

*****

Scott Wallace writes regularly about Laguna Bacalar and the environs on his website, BacalarMosaico.com. If you are planning a trip to that area, be sure to check out his website for events, hotels, and articles like this one about the area.

Amigos de Sian Ka'an is an organization that works to preserve the Sian Ka'an Biosphere... a worthy cause if we ever saw one.

And in case reading this has made you curious, here are the lyrics to that song.

Comments

Working Gringos 17 years ago

Oh, DUH!! Thanks for the correction... you are absolutely right!!

Reply

Alan 17 years ago

A great article accompanied by excellent photos, but one clarification; the article says;

"Located in the nearly flat southwestern corner of the Yucatan Peninsula, Laguna Bacalar is an extraordinarily beautiful lake and the second-largest freshwater lake in Mexico."

If it's on the Carribbean, doesn't that make it the southeastern corner?

Reply

(0 to 2 comments)