Living and Dying

As relatively novice expats, for the last five years we have harbored a secret little worry that if something goes wrong with us medically, the chance of disaster is higher here in Mexico than it might be otherwise. Being the adventurous risk-takers that we are, we have been willing to live with that worry. Of course, we aren't stupid risk takers. We've been to doctors here and been pleased with almost every experience. But we've never had a major health catastrophe, and ojala (God willing), we won't have one for a long time to come, if ever.

This August, two female members of the expat community in Merida unintentionally served as guinea pigs for the rest of us, developing medical conditions worthy of hospitalization. Their experiences and outcomes have served to mostly comfort us, and have certainly been educational. And in the spirit of this website, we are going to share with you what we have learned.

To protect their privacy, we'll call these women Snra. Una y Snra. Dos. They are both Canadian citizens living in Merida with residence visas. Their real identities are not as important as the events surrounding their lives these last two months. Let us add that we were on a roadtrip when all of this was unfolding, but have done extensive interviews with some of the people involved to be able to recount their stories to you.

Snra. Una is in her early sixties, has been living in Merida for many years and a well-known figure in the expat community. Before living in Mexico, she had lived in Guatemala. For the last few months, she had been living in her downtown colonial home while supervising some extensive renovations. Sometime in July, she came down with a pretty nasty virus that made the rounds here this summer, laying people up with coughs, congestion, headaches and fevers for two to three weeks. Snra. Una contracted this nasty flu but she didn't get better after two or three weeks. Sometime in August, she ended up asking her friend to take her to the emergency room.

They drove to one of the closest emergency rooms in the Centro at Clinica Merida on Avenida Itzaes. According to her friend, the experience there was far from good. The doctors were harried and seemed overworked. Paperwork was spotty or non-existent. The facilities in the emergency room were spare. The doctor they consulted gave her an off-the-cuff diagnosis while standing in the hallway. Snra. Una and her friend, who had been a nurse in Germany, felt unimportant and unsatisfied. (We would like to note that others have had good experiences at Clinica Merida, including ourselves. But things change, and luckily, we don't visit hospitals regularly or often). After buying the prescribed medicine from the 24-hour pharmacy there, Snra. Una returned home to let the medicine do its work.

A day or so later, she called her friend and asked her to take her to the hospital again, as she was getting worse. This time, her friend decided to drive a little farther to the brand new Star Medica Hospital located north of the Centro just this side of the Periferico. Star Medica is a chain of hospitals throughout Mexico, including Morelia, Aguascalientes and Cancun, to name a few. Snra. Una was treated in the emergency room by apparently competent nurses and doctors, and was admitted to the hospital so that they could administer treatments and monitor her response.

While Snra. Una was in the Star Medica hospital, back in the Centro, Snra. Dos was developing strange and unusual symptoms (pains and vomiting) that didn't seem to be improving. She had heard that Snra. Una's friend had been helping Snra. Una and she called her to please come help. Cutting to the chase, Snra. Dos, who is in her late fifties, was driven straight to the Star Medica hospital at 3:00 AM where they were greeted kindly by a young man and ushered into the emergency room. The nurses there took her vital signs and called a doctor. The doctor ordered immediate pain relief and called for another doctor, a specialist. Within two hours, after being examined by a specialist, Snra. Dos was told that she should check in to the hospital.

It was at this point that she was asked if she had insurance. The friend was allowed to go down and sign the papers for her... and no, she didn't have insurance. The hospital asked for a deposit of $800 US, which Snra. Dos put on her credit card.

Both Snra. Una and Snra. Dos were in the Star Medica hospital in the same week. They were checked in to private rooms (the hospital only has private rooms, about 60 of them on three floors) which cost $88 US per day. Each day, they or their family or friends could go downstairs and ask to review all the charges to their account up to that point. The friend went through the printouts with a representative for clarification on any charges and says the hospital was very generous in lowering some charges and removing others. In her opinion, the billing system and procedures were very professional.

The rooms had air conditioning, television with a remote, faux hardwood floors, a comfortable chair and a couch for visitors (made up into a bed by nurses upon request), a private bathroom and best of all, peace and quiet. The nurses, according to Snra. Dos, were charming and happy, obviously loving their work. The orderlies were shy and helpful, and the cleaning crew came in twice daily to ensure that everything remained spotless.

Something we should point out here: everyone spoke Spanish. Only one or two of the doctors spoke English. This has been our experience generally. Most nurses do not speak English. But most doctors have done some amount of school or practice in the States and do speak some English. Still, if you don't have a pretty good grasp of Spanish, it is helpful to have someone along who does.

Snra. Dos continued to have tests to determine her problem. She told us that everywhere she went, the hospital was clean and modern. Tests came back quickly, unless they had to be sent to Mexico City, in which case they came back the next day. Finally, her doctor told Snra. Dos that she had a very blocked gall bladder and that she would require at least one surgical procedure. If she elected the second procedure, removal of her gall bladder, then she would not be plagued by this problem ever again.

Snra. Dos elected to undergo both surgeries. She told us that her doctor, who did speak English very well, explained everything to her to her satisfaction and answered all her questions. He continued to communicate with her after the surgery to be sure that she was recovering well, even giving her his cell phone number and telling her to call any time of night or day. She did have occasion to call him once, and said that he answered the call and was informative and generous with his time. He explained to her that he had practiced for many years in the States, and that he understood how difficult it might be for people here who didn't speak Spanish. He offered his service to her and any other expatriate here to call or email him if they had any sort of medical questions (not just ones for his specialization, which is Oncology and Gastroenterology), and he would refer them to the right doctor or office for their needs.

Snra. Dos endured two surgeries. She related that the anaethesiologist was excellent, the operating and recovery rooms were clean and quiet and well staffed and she felt extremely well cared for. The morning after her surgeries, the doctor returned with two students from England who watched as he checked her out and asked her how she was feeling. He told her she could go home or stay another day if she wished, and she elected to leave.

Before leaving, Snra. Dos and her friend went over the bill with a representative and charged it all to her Visa card. The entire bill, including room, medicines, tests, water, kleenex, slippers and surgeries came to about $2,000 US. With the addition of the doctor's services, Snra. Dos was able to spend almost three days in the hospital and have two surgeries for less than $5,000 US.

Without insurance.

When we asked her how she would sum up her treatment, she told us, "except for the pain and expense, it was a wonderful experience!" She also said that her fear of "what if something happens to me down there in Mexico" had completely evaporated.

Were you wondering what happened to Snra. Una? She was still in the hospital. Doctors had tried many different treatments and medications, but she was not responding to any of them. Shortly before Snra. Dos checked out, Snra. Una slipped into a coma from which she would not awake. Doctors were unable to make any progress, and later that week, they suggested to her friend, who had been attending her, that they move her to O'Horan, the general hospital for Merida.

O'Horan, the oldest hospital in Merida, is located on Avenida Itzaes, approximately across the street from the Clinica Merida. It is where people go for treatment who cannot afford to pay for it anywhere else. The hospital is understaffed and underfinanced. The equipment is old. There are no private rooms, of course, and most people who are sick are being visited or attended by many members of their family. These family members must wait outside when they cannot be in the room, and the grounds of the hospital are full of worried family members who sleep, eat and cook outside the hospital as they have neither the time nor the funds to return home to their pueblos. Still, the same doctors who attended Snra. Una at Star Medica also checked up on her at O'Horan, as they are required to do service at the general hospital. So while the surroundings were not nearly as pleasant, and the equipment was not up to par, the doctors were literally the same.

Despite their care and ministrations, Snra. Una died a few days later of multiple organ failure. A mutual friend of ours and Snra. Una spent the next week wading through the paperwork required to get Snra. Una's family to make her a "next of kin" which allowed her to jump through the bureaucratic hoops to formally identify Snra. Una's body, have it transported to the funeral parlor and then arrange for it to be cremated.

We joined our mutual friend as she accompanied the body from the funeral parlor, housed in a former home of Felipe Carrillo Puerto on Calle 59, to the city-owned cemetery where it was cremated. The funeral parlor, Funerales Perches, is a pink confection of architectural wonder. The rooms inside are cavernous, with highly polished floors, beautiful arches, fotos of old-time Merida on the walls, and the obligatory casket display. The cost for the services of the funeral home was under $800US. This did not include a casket, which is not required for cremation. It did include transportation from the hospital to the funeral home, and then again to the crematorium at the municipal cemetery west of downtown Merida. The cremation cost about $300 (as noted by a sign in the office) and with all the papers in order, was a quick process. After our mutual friend signed the paperwork, we were escorted to the door of the Horno Crematorio (the oven), where we met the body which was brought out of the back of a black Funerales Perches minivan. Three men moved the body into the horno, one of them pushed a button and they told us we could come back in two hours for the ashes.

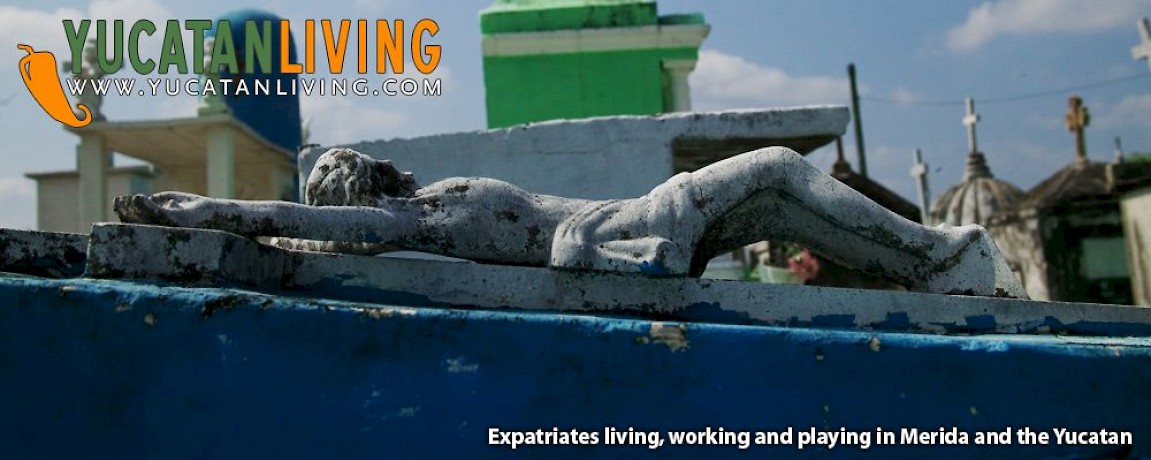

And so, Snra. Una made her salida (exit). Adios y buen viaje, querida! As we walked outside and sat on a bench, taking in the multicolored cemetery display with its spreading flamboyanes trees, we marveled at how strange life is and how totally pedestrian death can be. And how comfortable and close Mexicans are with death and dying. In Mexico, death is not hidden or closeted. Cemeteries are little towns painted in bright colors where the dead come to visit the living and where the living come to pay respects to their dead, bringing flowers (plastic ones last longer), liquor, coke, fotos and anything else that might bring a smile to their departed faces. Cemeteries are cheerful places in Mexico and every town seems to have at least one.

The next day, we went to the Star Medica hospital and gave blood in Ms. Una's name. This was not just a tribute to her, but a traditional way in Mexico to help the family (or in this case, friends) who paid the hospital bills. Snra. Una paid a 'blood deposit' when she was given blood in the course of her treatment. By donating our blood, we were 'paying' some of Snra. Una's hospital bill. We don't know what the bill came to, but it was substantial (we were told that Intensive Care at Star Medica is $550 US per day). Our experience at Star Medica was every bit as good as Snra. Dos had said. The place was immaculate. Everyone we talked with (in Spanish) was polite and cheerful. It only took one prick to find the vein (much appreciated!). And afterwards, we were treated to a fruit plate (or sandwich) and a glass of OJ at the cafeteria. Perfecto!

Maybe this isn't the kind of story you like to read, or maybe this isn't something you like to think about. But as we Working Gringo's get older, we realize that these things happen and involve issues we would do well to at least be educated about. We are grateful that Merida has a Star Medica hospital and that either through insurance (which is readily available and relatively affordable here) or our own resources, we can deal with it. We are grateful that there are such good doctors and caretakers here. And grateful that we are part of an expat community that bands together and takes care of each other like family.

For a list of all hospitals in Merida, as well as a list of English-speaking doctors, we suggest downloading the Personal Healthcare Guide at www.yucatanyes.com

US Consulate in Merida website (includes lists of doctors and funeral homes)