Princess of Yucatan: Secrets in Stone, Part II

"Quick, turn aside -- enter the village by the secret back path!" gasped the small messenger, looking all the while in terror over her shoulder. "Your grandsire -- he waits for you at the cave of the blue rock."

"Jaska, little one, what has happened?" cried Nakah, dropping her burden, and clutching the weeping child to her.

"I do not know," sobbed Jaska, "only everywhere is moaning and misery, and -- and the soldiers are among us, dividing up families. Hurry, hurry, Nakah! The good blind one says you must."

"Soldiers -- dividing the camp! For what?"

The portent of some dreadful calamity was upon her.

Mechanically, the girl picked up her basket, set it upon her head and, turning about, ran swiftly down a narrow way that branched off from the main path. This wound about through a tangle of jungle thickets and led at last to that secret meeting place of the bond-people, the cave of the blue rock. A cunning tangle of vines swung down across the opening of the grotto. Thrusting these aside, the panting Nakah crept into the cool semi-darkness.

Here, as the small Jaska had said, Copan was waiting. But such an impatient waiting! Back and forth across the narrow cavern confines the old man strode, stopping now and again to throw his arms above his head in wild gestures.

"Nakah, is it you? Ah, I know your footsteps -- come to me, child."

Quickly, and in a voice husky with anger, Copan told of this new grief that was to be laid upon the shoulders of the bond-people. To the old men and the women and the children would be left the burden of carrying on the slave-tilled farms, while all the strong men were to be taken away to the bitter life of the stone quarries. Already soldiers were tearing apart families for this separation.

"To the quarries -- the stone pits?" repeated Nakah in a whisper.

"Yes -- to the stone pits," went on the blind man. "The lordly Aztec priesthood would build a new temple to their war-god. All the strength of our tribe will be sent to their terrible quarries to toil beneath the lash and die in droves and -- "

Quite suddenly Copan turned around and grasped Nakah by the shoulders.

"Are you strong enough? Could you endure that life -- for a while?" he demanded.

"A woman -- a quarry slave! And you -- you could not stand it, grandsire, at your age, with your eyesight gone -- "

Nakah fell to the ground in a spasm of distracted weeping.

The old man gently raised her.

"Nay, trouble not over me. With my great size I am yet stronger than two men. Heavy labor will not kill me. But, Nakah, I fear for you. Fear to take you with me into the cruel punishment of the pits -- fear more to leave you at the women's camp. Your strange fair beauty is an eternal peril. Already these ravening Aztec priestesses have seized a score and more of our Itzan maids for temple service -- a service that sometimes ends in the sacrificial death of the waters. I cannot -- cannot leave you to that--"

"No, no!" Nakah's voice rose wildly. "Do not leave me to that. I will continue to be a boy, will go with you to the quarries."

She squared back her youthful shoulders, her strength rising within her.

"I can work -- I fear not that. I fear not anything, save separation from you."

Copan's wrinkled face lightened. He put a tender hand upon the girl's head.

"Yours is a brave spirit," he said and added, "come, let us make our preparations."

Quickly, as if to do this thing before their courage failed, the old man and the girl made their way to the hut that had been their home, gathered a few belongings into packs, and joined the long uneasy line of Itzan bondsmen that waited for the authority that would take husband from wife, father from children, away into the deadly exile of the pits.

Down the masses of moody humanity moved the Aztec quarry masters, each with a parchment-bearing scribe at his elbow, choosing the strong, setting aside the weaklings. Through the waning day and into the torch-lit night, the work went on.

Copan and Nakah, at the far end of the ranks, had a sorry wait of it. Would one be taken and the other left -- one taken -- one left?

Then the slave driver was upon them.

"Into the line of march, both of you," he ordered. Then, to his scribe, "Write down two for the stone-hauling gang of Tihua."

"Were they not better suited for water carriers, or such?" ventured the scribe.

"It matters not," answered the other indifferently, "Tihua needs two more to haul at the ropes -- none last long at it. Forward, all of you!"

If Nakah in the beginning could have foreseen what quarry life in its actuality meant, she might have weakened on that day of the choosing of the strong ones, might have made known her womanhood and let herself be returned to the farm village. But now that she was committed to the pits, she doggedly struggled on and on, through days of driven toil, and hoped that she could soon die.

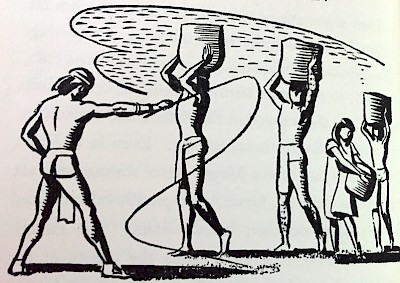

The stone quarries were all raw, crude ugliness, huge bald slabs of stone, dark caverns where men hacked and drilled still deeper into the earth, littered messes of rubble, flinders, broken implements and, drifting over all, the invevitable clouds of stone dust that forever irritated eyes and lungs. Some men worked up on high frail scaffolds, others tramped in a never-ending procession of water carriers, bearing dripping waterskins to be emptied on the ever-swelling wooden wedges driven into the drilled stone to rip it asunder. And still others, in that land that knew no beast of burden save man, were harnessed to huge low sledges laden each with a monstrous cut-stone monolith.

At the killing toil of sledge hauling labored Copan and Nakah. Already the harness thongs had worn galls across their strained shoulders. At each nightfall, the two fell exhausted on straw pallets and slept a sodden animal sleep till the call of the conch horns at dawn. But as months passed, and sore muscles became hardened to the strain, something of humanity came back to the laborers. At dusk around the glow of the cook fires, snatches of talk began to drift back and forth, even a wan joke or two was passed.

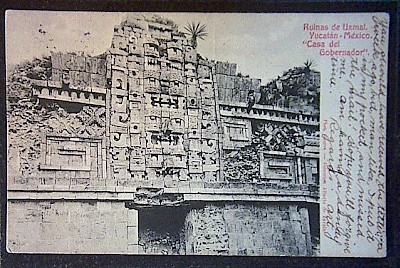

Within their hovel, old Copan strove to lift poor Nakah from the misery into which she had sunk. To comfort her, he told her tales as he had done when she was a child. On some nights, he softly "threw his voice and made the stones talk", a ventriloquial accomplishment with which he used to do tricks of yore to delight the small Nakah as a toddler. These childish things slowly took Nakah's mind from herself and her woe. Soemtimes, Copan, his mind turning back to the lost glories of his race, told Nakah traditions that had been handed down to him by the old Kakama -- last prophet of the holy men of Itza -- how Kakama had related to him the wondrous magnificence of the Old Empire, how half the wealth of the Itzans still lay in mysterious concealment, and how some day a mighty one would lead the Itzan people back into freedom.

But not always was Copan the strong comforter. There were black times when his heart failed him. Then Nakah, forgetting her own aches and blows, strove to cheer him, even as he had cheered her. In the dusk she sang to him the songs of the old Itza. Sometimes she brought forth the cracked, stained collection of broken tablets that had been her textbooks and, despite weariness, let her grandfather teach her again from the Mayan symbols. And one night, as they crouched for warmth close to a tiny blaze of twigs, Copan, reading aloud as his sensitive finger-tips traced glyph after glyph on the stones, came to a new set of inscriptions -- the inscriptions on the tablet fragments brought to Nakah that last day she had waited at the jungle trail. During the miseries of many moons, they had lain forgotten and unread.

Now, as he translated them, Copan dropped suddenly to his knees.

"Our gods be praised --" he began a whispered chant of thankfulness, "It is found -- the record so long sought -- the way to freedom opens --"

Then under the strain of excitement, the gaunt form of Copan the Blind fell forward in collapse.

*****

Editor's Note: This is the third in a series that is a serialized reprinting of a novel that we found on eBay: Princess of Yucatan by Alice Alison Lide, published in 1939 by Longman's, Green and Company out of New York and Toronto. The book was obviously researched heavily, as there are numerous (and interesting) references to Mayan lifestyles, locations and spirituality. Original drawings are included, which are attributed to Carlos Sanchez M. You can start at the beginning here.