Writing Checks in Mexico

We've written about banking and dealing with banks. But there is one thing about doing business in Mexico (not necessarily just in the Yucatan) that deserves an article of its own: cheques! (that's pronounced "chek-ays"). In the States, we write checks without thinking about it. In the States, we've had checks cashed that had the wrong date on them, where the number didn't agree with the written amount... we've even had checks cashed that we forgot to sign! So when we started running into the Mexican way of dealing with checks, we were totally unprepared. In the interest of preparing our readers, therefore, we offer up this synopsis (or is it a rant?) of our hard-won lessons.

Checking accounts - Opening a checking account in a Mexican bank? Leave yourself at least two hours and bring a friend, a good book or your iPod. Opening a checking account, like many other things in Mexican banking, takes time and patience. If you don't speak Spanish, this is one event for which you should persuade a friend or colleague who does speak Spanish to accompany you. Most banks do not have a lot of English-speaking employees, and there is too much at stake to let something go wrong.

You should be prepared with your passport and probably a few good copies (just to save time). You should also have your FM3 or FM2 visa, especially if you plan to open a business account. Be prepared to sit while the bank clerk opening your account makes multiple phone calls, some of which are surely about what she is planning to wear tonite. Be prepared to sign your name multiple times exactly the same way... try not to be self-conscious or mess up your own signature. Go ahead, we dare you not to! Make sure your signature matches the signature in your passport. You're going to need that trusty signature to be true to form in the future, so don't hesitate to practice in advance.

Checkbooks - Checkbooks are called chequeras. They are closely controlled here. You'll get your first one when you open up the account, but it won't have your name printed on it and not everyone will take those checks (similar to the situation in the States). But don't expect the ones printed with your name to be sent to your home. Instead, they will be held at the bank for you to pick up. And unless you have signed a letter designating your friend or office assistant to specifically pick up a checkbook already at the bank, you have to go to the bank yourself to get them. You have to show your ID (passport) and you have to sign for the chequera.

If you pick up two or three chequeras at a time, be sure to use them in order. If you don't (and we learned this the hard way), you cannot go back and use a chequera with lower numbers on it. That chequera has to be voided, by writing Cancelado (canceled) on each and every check in the book.

Before you write a single check from a new chequera, there is an important step you have to take that we just don't do in the States: you have to call the bank and activate the chequera. The number to call is usually on the front of the book itself, or on the bank's website. Of all the things that we can do on our company's new bank's website (HSBC), activating a chequera is not one of them. For that, we recently had to call the bank, provide our clave (which means "key" and is a unique number given to your account), our PIN number and talk to a representative. The representative asked us at least six security questions, and also wanted to know the range of check numbers in the chequera and if every check was in the book. If you write a check before activating the chequera, that check is no good and no bank will accept it, even if the payee doesn't try to cash it until after you have activated the book. Somehow, the bank has spies and they knew that we recently wrote a check to someone and THEN called them to activate the chequera. Sure enough, that check was returned, along with a nice little charge of $150 pesos.

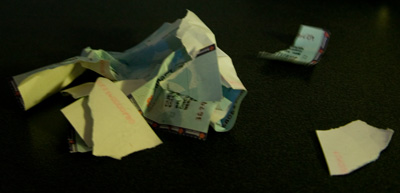

Writing checks - Even after five years here, we make a point of concentrating very carefully when we write checks. And still, we tend to make mistakes and have to void a lot of checks. Why? Because the slightest error will cause that check to be unusable. You cannot cross out anything on a check, whether or not you put your initials next to your correction. If you write something on the back of the check (such as your account number to deposit it, for instance), and then cross something out, that voids that check.

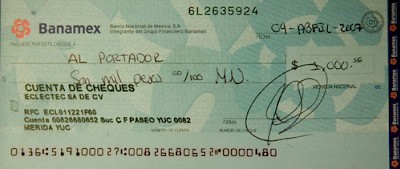

You must be careful to write the correct name of the person to whom the check is addressed. You must write everything in Spanish, of course. We have had checks rejected because the date was written in English (April instead of Abril, for example).

The amount of the check must be written out correctly, and if you spell a number like dieciseis (16) wrong, the check will be returned. You must write "pesos" after the written-out number or the check will be returned. You must write the number of centavos (cents) and then follow that with M.N. (Moneda Nacional), even though every check we've seen had "Moneda Nacional" printed on it below that line.

Then you must sign your name the same way every time. And that signature has to look the same as the one on your passport and registered with the bank. If you wrote out your middle name on your passport, then you have to do the same when you sign up for your checking account. And every time you write a check, you must sign your name exactly the same way. We can't tell you how many times we've had checks returned because someone didn't like the signature. Every time we write a check now, the suspense builds... will we do it right? Did we hesitate too long? Dot the "i" in the wrong place? Check-writing brings on a bad case of performance anxiety these days.

Tricky Amounts - Want to write a check for over $100,000 pesos (not unusual if you are building a house). At our personal bank (Inbursa), we cannot write a check over that amount unless we clear it through the central bank. Actually, they call it proteción. After we write the check and before it can be cashed, we must call the 800 number of the central bank and request proteción for that check. After asking six to ten questions to confirm our identity (including what type of account we have, who the beneficiaries are, etc.), we are asked for the name of the payee, the amount and the check number. Since the conversation is undoubtedly taped, they repeat this information about three or four times to make sure they have it right. Then they pass you on to a supervisor, who CONFIRMS the information in Spanish spoken so rapidly that it makes our head swim. All we can do is say "si" a lot and hope she's right. With our last bank manager, the payee (our architect, usually), had to also go to the manager and sit there while he called us to confirm that we did indeed mean to write a check for this amount to this obviously nefarious, middle-class mother of two. After all that, he would then finally allow her to cash the check. He has since been replaced by a more amenable guy who has not made la arquitecta go through that extra step. Also, since we're on the subject, you cannot write an al portador check for more than $100,000 pesos. Or is it $150,000? We forget. We only write checks like that after long enough intervals of time to have totally forgotten that we can't do it. Naturally, they are returned.

Accepting checks or cashing checks - Likewise, when you accept a check as payment, be careful that all these same rules are followed by the person writing you a check. Unless you need a check written in your name for a specific purpose (usually tax-related), most times people will simply write a check to Al Portador (to the bearer). An al portador check can only be cashed at the bank which has the account. Checks written to your name can be cashed at your own bank (if it is written on a check from another bank) only if you have enough cash in your account to cover it. Checks written to your name can be deposited to your account, however.

Sometimes, people would rather just deposit what they owe you into your account. This works well for people that live in a different part of Mexico. And it also works well for people who want to save money. Most banks charge a service fee of about $1 USD per check, in addition to a monthly checking service fee. We have heard that the government has recently decreed that no-cost checking accounts have to be made available to low-income clients, but we have not seen evidence of these yet.

USD checks - Have a check from the United States written to you and need to deposit it here? Imagine the reverse. Imagine that you have a check from Mexico that you want to deposit in a US Bank. Not going to happen. Well, here in Mexico, some banks actually allow you to open and maintain US dollar checking acounts. Those accounts easily accept other Mexican checks written in US dollars. But a check from the US written in dollars? That could take up to three weeks for approval. Frankly, we think it's a miracle it happens at all. Our one experience with a dollar checking account is that they are expensive and in the end, for us, not worth it. Many people apparently have dollar accounts (even Mexicans) because they don't want all their money in pesos. That's a legitimate choice, but not for a checking account. We've since closed ours.

Bouncing Checks - Try not to go there. Try very hard. A bounced check (called cheque de hule, or rubber check) in Mexico not only costs a lot of money (sometimes as much as $100 USD) but it can also cause more problems than a bounced check in the States. We bounced a check once, early in our residence here in Mexico, written to a major store (Office Depot). In addition to covering the cost of the check and the hefty penalty, we were advised to pay $1,500 pesos to "clear our credit" with that particular vendor. We decided to do that and paid the $1,500 pesos. We have still never been able to use a check at Office Depot in the last four years.

Statements and Balances - Your account statement will be sent to the address on the checking account. Want to change your address? You must go to the bank yourself and bring a comprabante (a utility bill - JAPAY, CFE or Telmex - sent to you at your new address with your name on it). You can't send someone to do this unless he or she has a signed letter from you. Want to consult your balance before you write a check? You can use the Internet, if you have your passkey. The passkey is a plastic gizmo that usually comes on a keychain and is sent to you at your address. It calculates a unique code every time you press the button (they all work a little differently), and you need that code, your password and your logon to get into your account. With one of our banks, you also need a clave (key), which has to be changed about every three months. Don't use a computer and want to check your balance at the bank? You'll have to stand in a special line to do that, because bank tellers don't know your balance and cannot check it.

Closing A Checking Account - We recently tried to close an account and this particular account was a business account and had two debit cards associated with it. We spent over two hours at the bank but were unsuccessful. Honestly. No one in the bank could agree what the balance was. We went to multiple windows, talked to multiple people and in the end, we gave up. We wrote a check the next day for what WE thought was in the account, and received our money. Whatever money is still left in the account will be eaten up within a month by service charges. We hear that if there is no account activity for six months, that the bank closes the account automatically. We've decided to test the theory rather than spend more of our precious time at the bank.

Security - As you might have deduced by now, Mexican banks are completely over the top when it comes to securing your account. Perhaps there have been more cases of bank fraud in Mexico than in the United States. Of course, we've seen no evidence of that. We think it would be very difficult to work your way around the measures banks in Mexico take to secure your money. In other words, the wheels of finance grind slowly here. The basic rule of thumb in Mexico is, if you don't need to use a check to pay for something, don't do it! It costs more money than it should, and the process itself is fraught with frustration.

In Summary - You might find these measures bothersome at times (heaven knows, we have!) but when Working Gringa's purse went missing recently, the fact that our chequera was inside didn't bother us one bit. We can barely make our own checks work, so you can imagine how hard it would be for someone else!