Forest Blindness

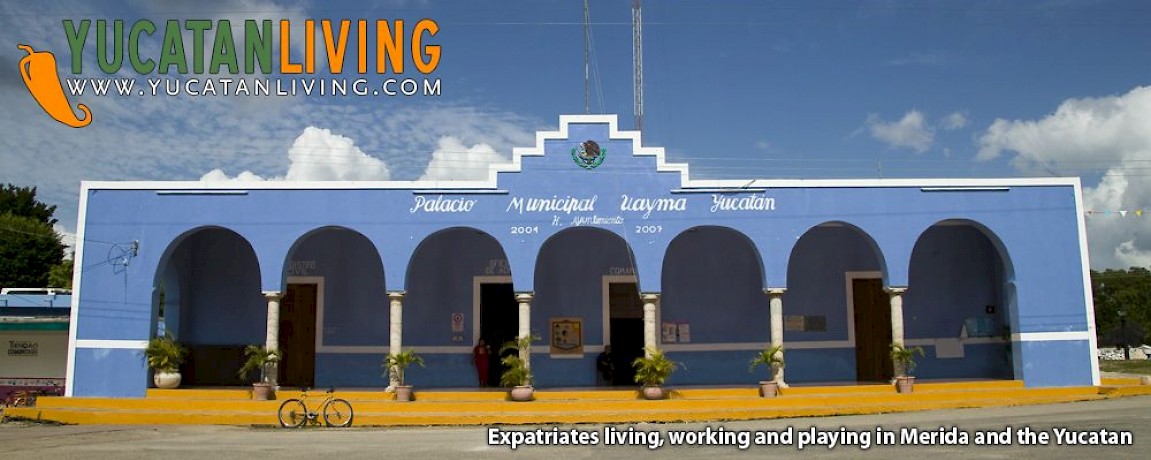

I own a piece of land in the middle of the Mayan jungle in a small pueblo near Valladolid called Uayma.

I bought land here because I love the church. But soon after my purchase, I fell in love also with the people.

Miguel Xooc is my unaware Mayan Professor and my helper. He calls me regularly to tell me every detail of what happens in this isolated and abandoned-by-me piece of land. He gets extremely excited when I come to visit my land. He shows me all the progress he has made in keeping the jungle away from the small partially-destroyed constructions of the Hacienda home that used to be there. While I am gone, he keeps track of every wild animal he sees and of every snake he kills. He even saves their skins for me.

I had to tell him to secretly inform me of all the details of what he does and especially to keep any animal skins away from my wife, or I will never convince her to move there in our retirement!!!

Last weekend, he told me that he had discovered a cave. He anticipated my desires to see the cave, and so he created a path through the jungle so we could walk with my son and his friend to explore the cave.

The cave was about one kilometer from the entrance of the lot, which means that he really worked hard to create this path. While we were walking, I told my son to look at the wild orchids blooming on tops of the trees. While we were looking at the tops of the trees, Miguel warned us to watch our steps and be careful of the thorns of one of the branches of the trees he cut earlier.

"What do you call this tree, Miguel?" I asked him. He said “…it is a Tzubim." We continued walking until I saw an identical branch and I warned my son's friend, telling him to be careful with the tzubim. Miguel immediately corrected me by telling me, “No, Patron, that is not a tzubim, that is a chimmay!“ "How would I know? They look all identical to me,” I responded. Miguel could not believe that I was not able to tell between such tremendously evident differences.

He decided in that moment that he was going to give me a botanical tour and he started to name and describe every tree he saw in this densely thick forest. “…So, Patron , this is a chaka. Look how red the wood is! It has a very soft wood. Now, look! This is a dzilzilche. This has very beautiful shells around its trunk. This one is a chacté and it has bigger shells around its bark and it has a very red chulul. "Hey, Miguel, stop there! What is a chulul?" Miguel stopped and turned to me. "Chulul means 'heart' in Mayan. The chacte's chulul is very red and its wood is very hard. This one here is a bacabché . In this one, the trunk is very smooth. It does not grow thorns and its chulul is brown."

Then Miguel got extremely serious and told me ”Patron, this is a chintoc." Miguel introduced me to this tree as if it were a person. “This tree is so hard that it breaks axes."

We slowly continued moving into the forest when we found more than fifty flowers laying on the floor. Miguel told me that those are the flowers of the piim . He told me that the piim tree has many thorns, and its flowers make bees crazy. Then he pointed to the top and there they were: hundreds of flowers coming out of the branches like a miracle. I asked Miguel why bees get so crazy about these flowers. He took one off the ground and asked me to smell it. In that moment, I joined the bees as the most incredibly intense and unexpected vanilla essence escaped from that flower.

We moved on and he pointed at a tree and told me “That is a mahahual. This tree’s bark is so thick that we use it for wrapping tamales." As we continued, we walked next to a tzubim and Miguel told me "from experience" that this tree has such big thorns that if you step on one, you cannot sleep all night long. We continued walking and passed a chimmay . He told me that the chimmay has a "very, very hard wood with an extremely brown chulul " but it compensates for those sins with very beautiful fruits.

As we continued walking, he describes trees with names such as pomoCHE, bacabCHE, chinCHE, ikiCHE, piniCHE and yaxCHE. I asked why most names end with 'che', and he explained that che means 'wood'. "The first part of the name describes the type or purpose of wood we Mayas give to a tree. One is 'the wood that cures', or 'the wood that hurts', 'the wood for shelter', 'the wood for the gods'." While he described each tree's features, I was able to get close to them, to look at them and to touch them. I started to detect their subtle differences as Miguel explained to me what they are used for. And then we found a chechen. As I approached that tree, a scared Miguel yelled at me to stop. “No, Patron, do not touch that one. The bark is highly poisonous. If you touch it, you will get a terrible itch and the swelling will be unbearable." Good to know.

As I walked and continued to be impressed by the height of the thousands of trees, I could not help but ask Miguel, "How do you know so much about all these trees?" Miguel replied, “We are all Maya... the trees and the people were born here. For us, knowing the trees is like recognizing a family member.”

Overwhelmed by the immense variety and his intimate knowledge, I ended our tour by asking: “And who planted all of these trees?” Miguel, with absolute conviction answered, “God, of course”.

*****

In real life, Rodrigo Rodriguez is a lawyer for www.yucatanvisa.com.

Comments

Mirah 8 years ago

Thank you for sharing this article. I felt not only the deep love that Miguel has for the land, but was also moved by his willingness to share his ancient knowledge.

Reply

Toni 10 years ago

Love it!!

Reply

Peter de la Cour 11 years ago

Some months ago Rodrigo took me with him on a trip to view some properties he wanted to look at. One of the plots we saw was this one that he later bought. About 6 weeks ago Rodrigo invited me along with 4 other friends to see what progress he had made with the land and to show us it’s potential. We were met there by Miguel and his wife and daughter who prepared a delicious lunch for us. Rodrigo said he wanted to rebuild the hacienda building where only the somewhat dilapidated walls were standing, but otherwise pretty much keep the plot as it was rather than tame it and change it into a man-made design. He said: “It’s wild but beautiful and I want it to remain like thatâ€.

Miguel led the way and took us along the neat paths he had recently cleared in the jungle. He gave us a master class in tree recognition and tree lore. At first sight all the trees looked pretty much the same to me. All had rather thin trunks, were not very tall and the foliage seemed pretty uniform. But as he stopped before first one tree and then another, it became evident that they were in fact very different. He gave us the Mayan names of the trees and explained what their names meant. Then he examined the bark, the branches and the color, size, texture and odor of the leaves and the fruits. Soon it became apparent that the jungle is not only a living forest, but also a pharmacy, a food store, and a raw material for the construction of houses and the making cooking utensils, sculptures and other artefacts. The forest and the animals, birds and even insects who live there are not only a slice of real life, but also a source of myths, fairy tales and richly symbolic in many different ways. Several parts of the trees we examine had medical properties. Miguel pointed out that the bark of one trees was poisonous to humans and that we should definitely avoid even touching it.

Miguel had a deep knowledge of all aspects of the forest. It was evident that he felt completely at home there, and that he was communing with nature. When we left I had the pleasant sensation that I had made tentative friends with the trees we had examined. Miguel had taken cutting from several of them and neatly arranged them in rows in a tree nursery, so that he could plant more trees when he wanted to.

As we left Rodrigo and I decided that we would soon return, rent some horses and explore the forest on horseback. I am very much looking forward to this adventure.

Reply

Heather Hunter 11 years ago

A lovely article to have found on the internet today. I am going to stay in a rural village in Quintana Roo next month and am looking forward to learning about the area. When you wrote that your guide said be careful not to tread on something, I thought it was going to be a snake. Being from Canada I am not used to snakes and I am afraid of them but I am going to conquer my fear because I love the friendly Mexicans so much. Gracias.

Reply

Gene Kelly 12 years ago

Also very interested in becoming familiar with the Yucatan trees. Any advice or direction on where to find information? Building and intend to live in the jungle

near Tulum.

Reply

Madai Batres 12 years ago

Loved it!!

Waiting yet for the book! ;)

Reply

Jennifer 12 years ago

What a beautiful article! Looking forward to more.

Reply

Ayn Cabaniss 12 years ago

Interesting article! Would love to have seen some photos of individual trees and possibly some Latin or common English names to go with the Maya ones. Never was able to find a decent book on local trees while living in the Yucatan.

Reply

Profesor Mike Fehily 12 years ago

Captivating and engaging. A living reminder of how we city folk need instruction from our indigenous "teachers" about the life of the jungle. Their synergy with nature is truly an inspirational talent. I look forward to more from "Patron" Rodriguez and the tales of Miguel "the Mayan Professor" and especially about "the tree that cures". Which one was that?

Reply

(0 to 9 comments)