Building Our House VI

It’s been so long since we’ve written about building our house, you may be wondering if anything is happening at all. We are here to assure you that a lot is happening… so much, actually, that it’s been everything we can do to keep up!

These days, when people ask us, “So, how’s the house going?” our unqualified answer has been “Great!” We’ve had a real lucky streak, a complete 180-degree turn from how things were about nine months ago. We couldn’t be happier with the architectural team of Mercedes Sanchez and Alvaro Cervera. Our project is still within budget, despite some changes that we have instigated. The project is also about a month ahead of schedule, something we are not expecting to continue, but nevertheless, an unusual and welcome circumstance.

Every Tuesday and Thursday, we meet with our architects at the site and walk around, monitoring progress, discussing issues and making dozens of decisions, large and small. Every two weeks, we sit down with Mercedes who gives us a complete accounting of how the money has been spent, so we have maintained visibility on all the costs. Our architects pay the masons based on work accomplished, not on time spent. The detailed paperwork this entails is included in the percentage that we pay the architects, so it doesn’t cost us anything extra, and for this we are extremely grateful. It allows us not to worry about whether or not anyone is working quickly or slowly… we can all just focus on doing a good job and getting it done.

Also, the architects have been great collaborators and pleasantly flexible. If we want them to go through the trouble and time of ordering some supplies, they charge their percentage. If we want to buy something directly, they have no problem with that. Thus, we have been able to save some money by buying and paying for things like tiles directly from the manufacturer.

The team of masons and others that Mercedes and Alvaro have working with them are an impressive group of dedicated craftsmen. They work with smiles and concentration. They don’t drink. They show up on time (and most of them drive to Merida together all the way from a pueblo called Seye). They take pride in what they do, with good reason. The workmanship, as well as the speed with which they have been working, has been undeniable and enviable. We’ve compared the quality of the plastering, floor-laying and tile work with every house we’ve lived in here and every other house we’ve seen, and we can comfortably report that we’ve not seen better workmanship nor work ethic.

Our professional relationship with Mercedes and Alvaro has been by the book. All the permits were obtained before they began work and the permits are affixed to a bulletin board that is set up at the front of the building in case an inspector comes along. Social security has been paid for all the workers, so that when two different workers were injured on the job (both had something fall on them), they were taken to the hospital and treated with no questions asked. They each stayed home to heal and were paid during their absence, but nothing extra was required from us. We have worked within the system and it has worked for us and for the trabajadores (workers). Not only have all their medical needs been covered, but contributions have been made to their future retirement and to their housing funds.

>

The months of July and August are typically slow months here in Merida, a tradition called la temporada. Everyone who is anyone goes to the beach and Merida is a shadow of its former self. We almost always stay in the city during this time (we don’t own a house at the beach), and we’re happy to say that our workers and our architects were here this summer too. The workers took a few days off for the annual fiesta in their hometown of Seye, and the architects took their children to Disneyworld for a week. But other than that, business has continued as usual and a lot of work has been accomplished.

Even the heavy rains this past month haven’t slowed us down, as the roofs were all poured before the rains started. So when it rains, work is done indoors. There has even been an advantage to the rains, as they have allowed us to see where any leaks are and fix them before we move in. The leaks, by the way, have been minor and the drainage systems that were designed and implemented have worked perfectly. After these last very heavy rains, we had absolutely no standing water anywhere on our property.

So let’s take a tour around the house and see what’s been going on since our last report…

Los Entrepaños

All colonial homes in Yucatan and even many modern homes feature built-in, concrete shelves and counters in the kitchen and bathrooms. Ours is no different, but in some cases there is a modern twist.

The conventional way to build a concrete counter here is to build a form out of wood, lay in iron reinforcement, which is smallish rebar and wire mesh, and then pour concrete into the mold. The concrete is plastered over with a layer of smooth, white cement, often with a colored pigment added. The last touch is to polish the final coat to a nice luster.

However, in some cases, such as the library shelves in our upstairs bedroom, the weight of the concrete would add stress to the floor, which our architects decided could be avoided by using a modern product called Panel-W, shown in the photo. This is a lightweight Styrofoam core surrounded by a wire mesh that is held together by wire struts in the shape of the letter “W”, hence the name. This material forms the basic shelf and can be cut to conform to any design. It is then covered with three coats of plaster, much the same way as the walls of the house. It can be finished using the same techniques for standard concrete shelves.

Of course, no Mexican kitchen or bathroom counter would be complete without some kind of tile. All of our counters have back-splashes fashioned from Talavera tile, which is most often procured from the city of Puebla. The one exception is our master bathroom. Its modest back-splash is of tumbled Ferrara marble, which we are also using on the bathroom floor. We originally purchased this marble for a renovation in California, but lugged it all the way to Merida in our car as a sentimental embellishment for our new home here. Since Ferrara marble comes from Italy, whose architects influenced the design of colonial homes in Merida, it is not particularly out of place.

Often, the concrete or Panel-W counters and shelves are designed to enclose wood shelves and cabinets. Our kitchen and some of our bathrooms will conform to this tradition, as well.

Tejabanes

Our house design calls for several indoor-outdoor spaces, typical of most tropical homes, and two of these are covered by a tejaban, or red tile roof. One of these areas is the terrace that joins the inner courtyard to the kitchen. The other tejaban covers part of the upstairs terrace outside the master bedroom.

There are two kinds of red tile available here. Where we come from, the Spanish preferred to use the half-circle shaped tile, which you frequently see in California and other parts of southwestern United States and northern Mexico. But due to the influence of French architects in Yucatan, the flat tiles of that era are the tradition here, so that is what we’re using.

A tejeban is usually constructed of large, wooden beams with a latticework of smaller wooden cross members that hold up the individual tiles. The tiles interlock to prevent leaks. The wood beams for our tejaban were cut from a hardwood tree called cedro, which is surprisingly heavy. The ends of the beams were cut in a distinctive shape and the leftover pieces were roughly the size of a bowling ball and weighed about the same. The wood of the cedro tree, (not to be confused with the cedar) is used for all kinds of carpentry here because it survives the humidity and the appetites of local insects. The cedro was once plentiful in Yucatan but is now mostly imported from farms in Belize.

The tejeban over the courtyard terrace is supported by concrete columns and arches, but the upstairs terrace floor could not support this kind of structure. The architects had to devise a way to support the rather wide tejeban somehow, which they managed to do by using a long steel girder that extends from one load-bearing wall to another, a distance of about 30 feet. The girder itself weighs several tons and we were curious how the masons would lift it to the second floor and set it on the walls. The architects were curious about it, too. Nobody offered a solution. For three days the girder lay in the yard while we discussed other matters with the architects. Then one day we all arrived to discover that the girder was installed high on the walls of the second story, without any explanation by the masons. Our curiosity has not been satisfied and we remain puzzled. We are reminded of the Maya legend about the technique the ancients used for lifting the massive stones to build their temples: levitation.

There was, however, a complication. One challenge of building a new house in the Centro Historico of Merida is that the property lines are not usually square. Rather than being drawn neatly on a map, legal property lines have been established over the years based on the placement and shape of existing structures, mainly because every house shares its exterior walls with the houses adjacent to it. Our property is flag-shaped and flares out slightly as you travel up the flagpole. This means that none of the rooms are perfectly square and only a few interior corners are 45 degrees.

When seen from ground level, the girder’s load-bearing wall on the left, which runs parallel beneath it, appeared to slope downward to the left, which would have made the whole tejaban structure seem to slope sideways. The wall wasn’t actually shorter at that end; it was really farther away, following an angle that was a bit more than 45 degrees and creating an optical illusion caused by forced perspective. The solution was to pivot the girder slightly forward on the left and backward on the right, then create a slope to the top of the wall, making it higher on the left side. The wall was then capped in a way that hid the girder’s true position. This solution cheats the eye from nearly every angle, so you can’t really tell that the beam is not on a straight line with the load-bearing wall unless you look along the length of the beam toward the wall, as if aiming a rifle.

La Alberca

The construction of our alberca, or swimming pool, has probably languished a bit, perhaps due to the typical slow down during la temporada, but also because pool repair is in higher demand during the summer months. Our “pool guy”, who actually represents a company called AguaLux, has not always responded as promptly as others, but progress has picked up since August and the plumbing and lighting is installed, and the final form of the pool is taking shape.

As mentioned in previous articles, the pool has been built mostly above ground, on the same level as the indoor sala and its outdoor terrace. The main reason for building pools above ground in Yucatan is obvious once you’ve lived here and taken a shovel to the soil: between one and three feet below the surface is solid limestone. Very solid. We’ve been told it extends between 50 and 70 feet down until you meet the aquifer. The only way to defeat this ubiquitous bedrock is with several weeks of devoted abuse using a jackhammer (or, illegally, by using explosives). We know this first-hand because a renovation a few buildings down from our office used the jackhammer approach for many weeks to carve out a pool only a quarter the size of ours. Needless to say, everyone on the block ran out of aspirin and patience after only a few days.

The pool’s foundation and sides are rough-hewn using stone quarried from the property and trucked in, glued together with mortar. The far end is about three feet deeper than the end near the terrace. There is a small, submerged platform on the terrace end for lounging in shallow water to read a book or play with the grandkids, should there ever be any (friendly hint to our children). This structure is overlaid with heavy wire reinforcement that the masons call “maya” and is covered with two layers of concrete. The rim of the pool is a solid pour on top of the stone foundation after the lighting and plumbing were set within a wooden mold. All of the pool equipment will be hidden within an enclosure at the far end, which will also serve as a “water wall” that feeds a lit fountain that flows into the pool.

La Cocina

A special delight has been watching the masons build the elements of the kitchen. One wall is covered with concrete shelves, finished in white cement with yellow pigment. The lower shelves will have wooden cabinets installed. The opposite wall has two long shelves with spaces for our stove and cabinets underneath. Above the spot for the stove, the masons have sculpted a large campana, a bell-shaped vent that is traditional in these colonial homes. Just steps from the stove is a pantry, with more shelves and two skylights. This is where we intend to hide the refrigerator. All in all, this kitchen will have more storage than any we’ve ever had.

The floor is a checkerboard pattern of grey and white tile, and in the center is a generous island counter made entirely by hand using concrete. This is where the sink and small appliances will live. Two large doors open from the kitchen to a covered terrace facing the inner courtyard. Much of the actual cooking will take place on this terrace, since we have come to enjoy many Yucatecan meals that are prepared a la parilla (grilled) over a mesquite wood fire, like arrachera and cebollas. Hmmm.

Los Pisos

The original part of the house that is being renovated did not have traditional floor tiles, and the majority of our construction is new. So we were free to choose whatever floor finishes we wanted. We love the mosaicos that are made in Yucatan (see our article, Love Those Floors!), so we were thrilled with the prospect of choosing the designs and colors of the tiles for each room. In the end, it was another lesson in being careful what you wish for, because the dizzying combination of available colors and designs almost drove us crazy.

We spent weeks laying out tile combinations using Photoshop but finally had to stop because it was time to order. We tried to stick with certain color combinations, but found we were still second-guessing ourselves, even as the tiles were being laid. Finally we have decided that we love most of our decisions, and like the rest. And by the way, despite our careful calculations, in the end we still had to go back and order more tiles. In one case, the manufacturer already had the extras and we could just buy and install them the same day. In another case, we’ve been delayed a week or two while they produce the tiles we didn’t order correctly the first time around. Luckily, this isn’t slowing overall progress.

As mentioned before, many of the rooms are not perfectly square, but the tiles are. In some cases, if you lay tiles all the way to the wall, they must be cut at an angle that is obvious and somewhat disconcerting. A traditional way to mask this problem is to lay a square tapete, or carpet, of tiles in the center of the room and fill the space between it and the walls with polished white cement. This is exactly what we have done in most of our rooms.

The upstairs floors boast a new but ultimately hidden innovation: blue balls. That’s right, there are thousands of tiny, blue Styrofoam balls mixed into the concrete to make the upstairs floors lighter than they would otherwise be. Our architect handed us a stone one morning that was actually a clump of hardened concrete made in this way. It was surprisingly lightweight but very tough. It reminded us of pumice, the volcanic rock that floats in water.

Las Puertas

There are over two dozen doors in our house. Some of these will be new, wrought iron doors, particularly when they have to protect us from the weather. A couple will be new, wooden interior doors, made of cedro to especially fit a particular opening. We always intended, however, to find and use as many reclaimed, hardwood doors as possible. This isn’t a simple proposition, because the traditional hardwood doors removed from colonial homes in Merida and sold through the antique stores are in high demand and it has become increasingly difficult to find them. We have managed to locate several that we are pleased to install in our home, including a rather rustic and unusual arched door with large iron studs that we’ll use as the back door to our office, leading into the courtyard.

If you are reading about our construction project for the first time, you probably don’t know that it was severely delayed and then postponed for several months while we attended a few courses at the famous School of Hard Knocks. After graduation, we were able to find our current architects and restart our project without any postgraduate studies, for which we are thankful.

One unexpected benefit of the delay was that a new store came to town, called Luna del Oriente, owned and operated by fellow expats, Jeff and Debra. For reasons we can’t quite figure out, they jump through the myriad hoops necessary to import reclaimed, hardwood doors from India and China, along with many beautiful pieces of furniture, statuary and other architectural details. The doors are made of teak and come from a part of the world that has a similar climate to Yucatan, so they are hardy enough to live here and fight off the bichos (bugs). What’s more, they are gorgeous, hand-carved works of art. We purchased several and have installed them upstairs for our bedrooms and bathrooms (shown here in plastic wrap).

La Tina

One of the required elements of whatever new house we were going to build was an outdoor bathtub, and we’re happy to say that this particular dream is coming true more beautifully than we had imagined it. Our bathtub is located on the terrace outside the master and guest bathrooms. It has been roughly shaped out of concrete block and then sculpted with layers of cement. We’ve designed an “infinity” tub, so it can be filled to the top, and overflow into a surrounding channel that will eventually be filled with white river rocks. Next to the tub is a lounge area for lying in the sun, or sitting and talking to whoever is in the tub. All of this will eventually be covered with a chicum finish, the same finish that will surround the pool and the outdoor banquettes.

Indian Nichos

Among the statuary imported by Luna del Oriente are some miniature stone altars from India. No two are alike. They are carved from different types of stone and come from different parts of the country. Each one has a niche where you can put a candle or an offering. We bought a few of these, and have incorporated them into the walls of the spa area surrounding the outdoor bathtub to add to the reverent and tranquil ambiance of that area. The overall effect we are trying to achieve upstairs is something we call “Yucatasian”, a marriage of the materials and construction practices of Yucatan with elements of Asian décor. We hope to feel muy tranquilo in these private spaces.

El Torre

Our house has two stairways for gaining access to the second floor. One stairway is inside and goes from the sala directly to the bedrooms; the other is an exterior “stair tower” that leads to the upstairs terrace, where there is an area for outdoor entertaining, as well as a service route to the laundry room and roofs. The stair tower is also a bodega that houses a pressurized water system, water softener and circuit breakers.

The stairs in the tower switch back 180 degrees halfway up, and are divided by an interior wall nearly 25 feet tall at its highest point. This wall seemed rather imposing, so the architects suggested that we might want to add some visual interest to it. We decided to cut out an arch and install a reclaimed wood beam on which we will hang an old brass bell we found at a local antique shop. In this way, our stair tower has been transformed into a bell tower and may someday compete with our two neighboring cathedrals. If you’re in the neighborhood and you hear a bell tolling at 5 PM, you’ll know it’s us, signaling cocktail hour!

Acabados

There are two acabados, or finishes, applied to concrete in Yucatan that are unique to this region. One is called kankab in Mayan or tierra roja in Spanish, meaning “red earth”. The southern part of Yucatan is rich in deep red soil, which can be mixed with water, white glue and a few drops of motor oil to produce a kind of paint that produces a very pleasant earthy texture and color when spread over white or grey concrete. The perimeter walls around our backyard have already been painted with kankab, which will allow it to age nicely before we move in. We plan to finish the courtyard fountain in kankab, as well.

The other finish is called chicum, the Mayan name of a local tree. A chicum finish is produced by mixing white cement with the resin boiled from the bark of the chicum tree. This makes the cement water resistant and gives it a creamy, marbled appearance. Chicum was widely used by the Maya to seal the surface of their temples and especially their chaltun, which are cisterns for capturing and storing rainwater. The hacendados adopted chicum in the construction of their buildings, as well. Two famous examples are Hacienda Yaxcopoil and Hacienda Tabi. From these and other examples (including a plunge pool shaped like a chaltun that we enjoyed in our former colonial home), we learned that chicum ages gracefully and is a good way to preserve concrete that will experience a lot of moisture. We plan to finish several outdoor concrete areas with chicum, including the bathtub, seating areas, the pedestal for the bar and the rim of the swimming pool.

Hierro Forjado

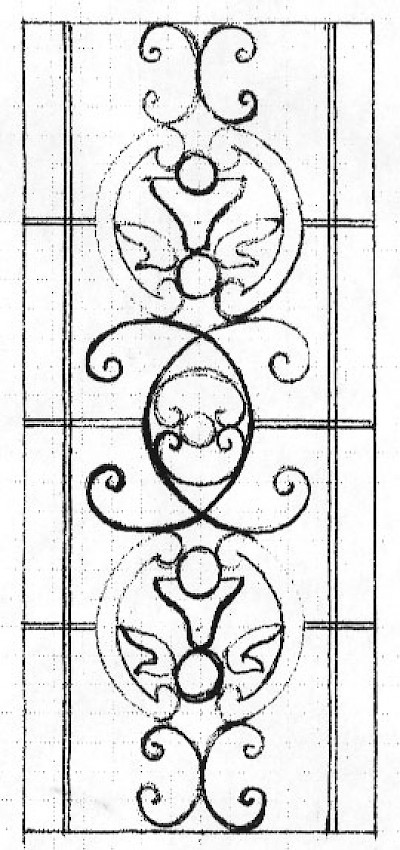

One of the more elegant touches found in Yucatan’s colonial homes is wrought iron. As mentioned above, there will be several large, arched wrought iron doors on the ground floor. There will also be a number of banisters and handrails along the stairways, not to mention wrought iron sconces and other lighting elements.

The sala is several feet above the dining room, in order to place it at the same level as the terrace and aboveground pool, so there will be a decorative banister dividing the two rooms to prevent falls.

Another common wrought iron feature is called a protector. These are wrought iron grills, often featuring elaborate designs, that cover windows and doors to prevent damage or theft, and sometimes, to prevent a wayward bird or bat from entering the house. Halfway up the interior stairway is a large window facing the backyard that will bring light into the stairwell, and it will sport a large protector.

We are fortunate that Alvaro, one of our architects, has a gift for creating lyrical wrought iron designs. His design for the stairwell window is shown in the illustration, and we can’t wait to see it installed. We’re also planning to have chandeliers made for the outdoor part of the pasillo, and we’ll be using his designs for those as well.

La Luz

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, our meticulous and bespectacled electrical engineer, Don Martin, has been supervising the installation of our rather complex wiring matrix for both the electricity and networking that we need to live and work. He has been asked to perform a series of miracles that involved moving outlets and lighting fixtures, sometimes only a few inches, other times across the room, because we did not anticipate how a minor change in a floor plan or a tile layout might impact the electrical plan.

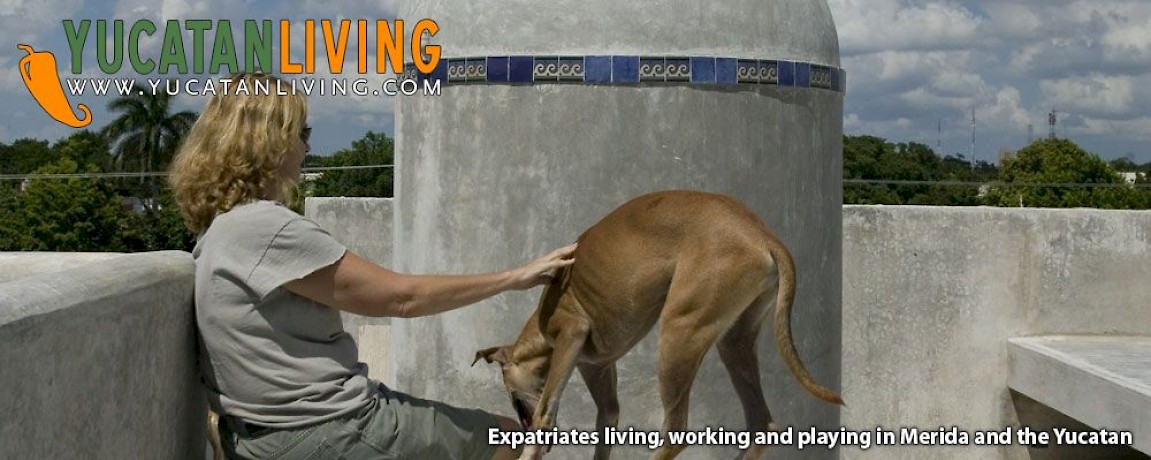

La Cúpula del Tinaco

Anyone who has visited Yucatan knows that most houses are crowned with one or more tinacos, which are large water tanks usually made of black plastic. The skyline of Merida is a parade of tinacos. We had noticed over the years that some homeowners build modest sunscreens over their tinacos, or in some cases even small shelters to enclose them. This is not really to reduce “tinaco blight” so much as to keep the sun from beating down on your water supply all day, which makes your cold water hot during the summer months.

We suggested to our architects that our tinaco should have some sort of enclosure, too, perhaps shaped like a cupola. We never imagined what the result would be and no plans were drawn up. Instead, the request was passed on to the masons, who took it upon themselves to craft what may be Merida’s finest tinaco enclosure.

From our rooftop, you can see the cupola and bell towers of San Sebastian, one of Merida’s oldest colonial-era cathedrals. Apparently, the masons were inspired to somehow compete with this landmark in the execution of our tinaco’s cupola. The photo shows the result, as yet unpainted. Now that this monument to gravity-fed, potable water systems has been erected, naturally there is talk of adding some dramatic lighting so it can be seen from San Sebastian at night.

The Human Touch

When we lived in California, we remodeled a Spanish Revival house. The project was mostly a two-story addition to the back of an existing structure, which had been built in the 1920’s. While the result was acceptable by most standards, it disappointed us. Why? Because try as they might - using the latest tools, materials and techniques - our contractors could not really match the workmanship of the original building.

It’s obvious to us that most homes built in modern Gringolandia are products of manufacturing, without the human touch.

With only a few practical exceptions, everything in our new colonial-style home has been made by hand, hecho a mano, from the plastered walls to the wrought iron, to the kitchen counters and the floor tiles. And everywhere you look in our new house, you can see evidence of human creativity, initiative and intelligence, rather then the so-called perfection of machinery. In our house, you see evidence of workmanship, something that has been defined as a human hand connected to a human mind, and most importantly, to a human heart.

To read the past progress of our house project, here are the links:

and

How to Build a House in Merida

Comments

Khaki 18 years ago

If work ever slows down for those masons (which I sincerely doubt) – they could make a fortune with La Cupola del Tinaco. What a great idea!

Reply

« Back (50 to 51 comments)