Yucatan's Connection to Texas, Part Two

Editor's Note: This is the second of a two part series in which the author explores the historical relationships between the Yucatán and the Republic of Texas. Byron Augustín is a former professor at Texas State University and we are happy to be the recipient of his research on this subject. For information about each photo, please click on the photo to read the informative captions. Enjoy!!

*****

Not Just On The Ground

Most discussions of the military operations carried out during the Texans struggle for independence from Mexico focus on the activities of ground forces. However, action on the waters of the Gulf of Mexico contributed substantially to the outcome of that particular revolution.

General Santa Anna

General Santa Anna made a grievous error by not listening to his advisors before marching to the Alamo. José María Tornel, Santa Anna's minister of war, pleaded with the general to wait until spring when the weather would be better and the Mexican Navy would be stronger. He argued that with a strong navy, troop reinforcements, munitions and medical supplies could be delivered to Mexican forces as they swept across Texas. Santa Anna responded that Texas had no navy and that control of the Gulf of Mexico would be maintained by Mexico. As one noted historian wrote,

This belief was one of the greatest errors that General Santa Anna would make, but over the years of recorded history, it has seldom been the case that an army commander has properly evaluated sea power.

Small Navy, Big Bite

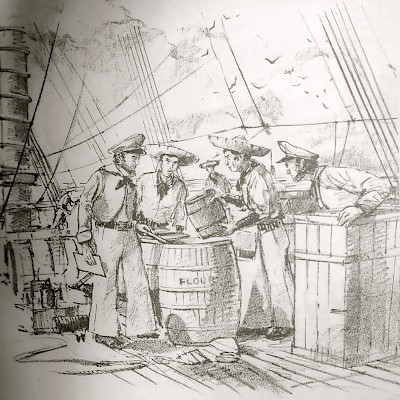

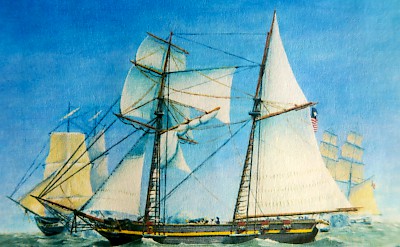

The General Council authorized the First Navy of what would become the independent Republic of Texas in November of 1835. That authorization provided for the purchase of two twelve-gun and two six-gun schooners. In January and February 1836, the Texans purchased the Liberty, Invincible, Independence, and Brutus. All four ships were cruising in the Gulf of Mexico before the Texans declared their independence, and all four vessels distinguished themselves during the course of the next few years.

Commodore Hawkins, in command of the Independence, cruised the Mexican coast between Galveston and Tampico, wreaking havoc on numerous small Mexican boats and taking any materials useful to the Texans. In mid-March he returned to New Orleans for refitting.

Meanwhile, the little Liberty, only 60 feet in length, engaged in one of the most significant encounters of the entire conflict. On March 6, 1836, while skirting the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, the Libery spotted the Mexican schooner Pelicano anchored in sheltered water in front of the old Spanish fort at Sisal. After the Liberty raked the deck of the Pelicano, Capitan Perez surrendered. When the cargo was inspected, the Liberty’s crew found more than 300 kegs of gunpowder hidden in large barrels of flour. They also discovered other supplies for Santa Anna’s army. The Pelicano was towed back to Matagorda Bay and the gunpowder and other supplies were sent to General Houston in time for the Battle of San Jacinto.

Later, the Liberty sailed to Galveston where it provided escort protection for the Flora, the ship that carried General Sam Houston to New Orleans for treatment of his injuries suffered in the Battle of San Jacinto. While the Liberty was in New Orleans, the decision was made to repair the ship before returning it to duty. As it turned out, General Houston was unable to pay for the repairs, and the Liberty was sold, reducing the Republic of Texas Navy to three ships.

On April 3, 1836, the Invincible, under the command of Capitan Jeremiah Brown, arrived at Matamoros. Here, he discovered preparations underway for an invasion by sea with reinforcements and military supplies for Santa Anna. With lightning force, the Invincible broke up the preparations by driving the Mexican naval vessel Bravo aground. She then forced the supply-carrying Correo Segundo back into port and captured the U.S. ship Pocket. The Pocket carried a false manifest and several Americans on board who were expecting to be commissioned in the Mexican Navy. Worst of all, the Pocket had a contract to transport Mexican soldiers to Texas. The attack by the Invincible seriously damaged the likelihood of a Mexican naval invasion to assist Santa Anna. Two weeks later, it did not matter as Santa Anna’s troops had been routed in the Battle of San Jacinto and had surrendered.

During the summer of 1836, the three remaining vessels were charged primarily with keeping the Republic of Texas ports open for commerce and maintaining a partial blockade of Matamoros. By September, all three schooners were in need of repairs and refitting. The Invincible and Brutus sailed to New York, and the Independence to New Orleans. By the time the ships returned to the Gulf Coast in April of 1837, the republic was being subjected to a Mexican blockade.

Disaster Strikes

Then, disaster struck the Independence. She had left New Orleans of April 10th, carrying a special passenger named William H. Wharton. Wharton was the Texas Minister to the United States, who had helped negotiate U.S. recognition of the Republic of Texas on March 3, 1837. As the Independence entered the mouth of the Brazos River, two Mexican brigs-of-war, the Vencedor del Álamo and the Libertador chased her upstream on the Brazos to Velasco. The ships could go no further because of the depth of the water. When it was apparent that continuing to fight would risk the life of their esteemed passenger, surrender was deemed the wisest option. It was the only time a vessel in the Navy of the Texas Republic surrendered. Captain Wheelwright and his crew were taken to Matamoros and placed in jail as prisoners of war. The Independence was commissioned into the Mexican Navy and renamed the Independencia. A few years later she became a part of the Navy of the Republic of the Yucatán, hoisting the flag of yet a fourth country. Meanwhile the Republic of Texas' Navy had been reduced to two ships.

President Sam Houston Versus The Navy

The future of the first Texas Navy would be challenged during President Sam Houston’s first term of the Republic, from 1836-1838. He appointed S. Rhoads Fischer as Secretary of the Navy. Fischer, who had watched the embarrassing surrender of the Independence at Velasco, envisioned a much more aggressive navy than President Houston. Houston, like many other army commanders, including Santa Anna, did not properly evaluate the role of sea power. In his mind, navies cost money and the young republic did not have currency for naval investments. His philosophy was much along the lines of the old adage:

...a ship is a hole in the water that you pour money into.

With this attitude, Houston informed Secretary Fischer that there would be no new ships. He also told him that if the Republic did not attack and harass Mexican vessels and ports, the Mexicans would leave the Texans alone. He gave instructions to Fisher to use the Invincible and the Brutus to cruise the Texas coast and protect shipping and Texas ports. Fischer and Commodore Henry L. Thompson, the Captain of the Invincible, decided that for the small two-ship navy, the best defense was a good offense. They devised an aggressive and audacious plan to take the fight to the enemy, instead of waiting for the Mexican navy to attack them. Aware that President Houston would never approve their plan, they did not tell him.

The Cruise to Yucatan

The Brutus, under the command of Capitan James D. Boylan, joined the Invincible with Commodore Thompson and Secretary Fischer aboard. Boylan received his orders from Commodore Thompson, while Fischer never imposed his position as Secretary of the Navy on the command. Instead he viewed his role as that of an observer who joined the cruise to help lift the morale of the sailors after the devastating loss of the Independence.

After escorting the merchant schooner Texas to Matagorda, they returned to Galveston. On June 11, 1837, the ships sailed east to the mouth of the Mississippi River, looking for a fight. Finding no Mexican ships, they split up, with the agreement to meet at Isla Mujeres near the northern tip of the Yucatán Peninsula. The Invincible headed south and arrived at Mujeres before the Brutus, which cruised by the western end of Cuba and on July 7, 1837, anchored off of Isla Contoy. On the 8th the Brutus joined the Invincible at anchor in the deep water off Isla Mujeres because of dangerous coral reefs near the beach. Over the next three days, the crews took small boats to neighboring islands, replenished their fresh water supply and collected a large number of turtles for fresh food at both Mujeres and Cancun. Today, Isla Mujeres is the site of a turtle farm (tortugranja) attempting to restock the numbers of ocean turtles.

The crews appeared to think it was all right to empty the turtle pens without paying the locals. The turtles were in great demand for sailing ships. Their meat was tasty and a turtle could be kept alive below deck for at least a year while their meat remained edible and fresh. When the H.M.S. Beagle stopped in the Galapagos Islands in 1835, Charles Darwin wrote about the crew placing 30 giant tortoises below deck for the ship’s continuing voyage to Polynesia. The governor of the Galapagos Islands told Darwin that he could tell which island the turtle came from by the shape of its shell. Many scientists believe that this information helped contribute to Darwin’s formulation of his theory of evolution.

Claiming Cozumel

On July 12 1837, the two-ship fleet sailed for Cozumel. Both captains noted how close to the island the ships could anchor. Today, large cruise ships appear to be anchored almost on the beach. After going ashore with the crew, they claimed possession of the island and fired a 23-gun salute. Then they spread out across the island to survey their newly claimed territory.

The captains were effusive in their description of the island, noting the healthy trade winds, rich soils, bountiful forests of mahogany and Spanish cedar, and an abundance of fruits and fresh water. Thompson wrote in his final report,

I am convinced that the island will be one of the greatest acquisitions to our beloved country that the Admiral aloft could ever have bestowed on us.

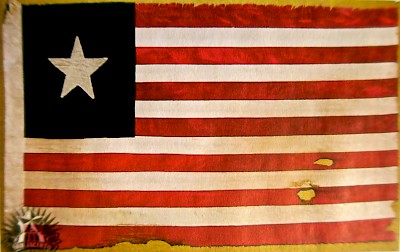

Before leaving, the flag of the Republic of Texas Navy was hoisted forty-five feet above the island and Captain Boylan reported that the inhabitants of the island swore allegiance to their cause. No one seemed to remember that Spanish conquistadors had claimed the island for Spain in the early 1500s. When you are collecting real estate for a new nation, apparently no one has the time to check ownership records.

Boca Iglesia and Ixchel

Sailing north to Isla Contoy, the small fleet stopped to check out the tiny island. They encountered no human inhabitants, but domestic animals were present and there was evidence that people had been in the houses recently. Best of all, they found several pens full of live turtles which they took on board for a supply of fresh food.

The next day they sent their small boats in search of a rumored town near Cape Catoche. In all likelihood they were looking for Ekab, which was a thriving Maya city when Francisco Hernández de Cordóba first visited in March 1517. After the Spanish built a large church with the stones from the Maya city, the name was changed to Boca Iglesia. Isolated, located in Hurricane Alley, and attacked by French and English pirates, the city was eventually abandoned. The Texans never found the city, but did return with clay images of females they found along the way. While they did not know what the images represented, they had seen the same images at Isla Mujeres near a Temple to the Maya Goddess, Ixchel. Ixchel, the Goddess of the moon, fertility, and motherhood was worshipped on both Isla Mujeres and Cozumel, and both islands were pilgrimage sites.

Burn, Sink and Destroy

Back at sea, they followed the Yucatán coast westward to Silan, now named Dzilam de Bravo, the rumored burial site of the French pirate Lafitte.

Boylan notes that they stopped at a village named Leuckwe where the mayor surrendered the village. (Maps of that time period show no villages by the name of Leuckwe near the coast.) On the 22nd of July, they captured the schooner Union loaded with valuable logwood. On the 24th a small group, including Secretary Fischer and Captain Boylan, went ashore along a beach they recorded as Chiblona. While they were exploring the area, a small group of Mexican Calvary rode over a sand dune and surprised the Texans. With less than 100 yards of distance between them, the Texans turned and ran to their boat. As the Calvary approached, Secretary Fischer drew a pistol and shot one of them, knocking him off his horse. The Mexicans returned fire but missed badly.

This was a turning point in the cruise, as up to that point, the Texans had not engaged in killing, burning, or firing their canons. Commodore Thompson, sensing the aroused emotions of his crews, gave the order.

To burn, sink, and destroy everything we came athwart.

The crew from the Brutus proceeded to burn two Maya pueblos along the coast. Burning the pueblos was an easy task, as the Maya nah houses were constructed mostly of tree branches and thatched roofs, which ignited and burned quickly. Continuing along the coast, they captured the Mexican schooners Adventure and the Telegraph of Campeche, before arriving at Sisal, the Yucatán’s major port.

Sisal, the Alacranes and the British

The next day, Commodore Thompson sent a canoe ashore with a letter for the Commandant of the old Spanish fortress, demanding money to prevent the destruction of the town. The Mexican Commandant did not reply. The Texans hoisted the flag of truce and with their smaller boats, towed the war schooners closer to shore. At 7:00 A.M., the Mexicans fired the first shot. The Texans lowered their truce flags and the battle commenced. For two and one-half hours, they exchanged fire. Most of the shots fell short because of inferior gunpowder. Little damage was done to Sisal or the Texan ships. In a sense the effort was like spitting in the wind. Not wanting to feel totally ineffective, before they left, they burned the schooner Adventure.

Their course from Sisal took them next to the Alacranes Islands. Here, they raised the Texan Navy flag and claimed the islands for the Republic of Texas. They cruised offshore and captured the schooner Abispa. Later, they captured the British schooner Eliza Russel, which was carrying uninsured goods to a merchant in Mérida. Commodore Thompson sent the Eliza Russel to Texas to have the Mexican goods condemned. When the British discovered this, they were livid, claiming piracy on the high seas. President Houston apologized profusely to the British, but the event set British recognition of the new republic back considerably. Commodore Thompson and Secretary Fischer would face Houston’s unbridled wrath on their return.

A Sad Ending

On the 12th of August, the Texas navy captured the Mexican packet schooner Correo de Tabasco. At Chiltepeque, they released their prisoners and received fresh water, fruit, and other supplies. On the 17th, they captured the Mexican schooner Rafaelita. Then they sailed to Matamoros where they hoped to engage the Mexican naval vessel Brazos de Santiago. However, their water supplies were running low and the seas were producing increasingly high waves. It was time to return to Galveston. The Brutus arrived at Galveston at 9:00 P.M., August 26, 1837. The next morning the Invincible arrived. Secretary S. Rhoads Fischer was transferred to the Brutus and Thompson ordered Captain Boylan to take the captured Correo de Tabasco into the Navy Yard. The tide was low and the Invincible’s draft was too deep to clear the channel. Unfortunately, before the Invincible was able to enter the yard, two Mexican armed brigs attacked her. Captain Boylan tried to exit the Navy Yard to come to the aid of the Invincible, but struck a sandbar. While trying to tow the Brutus off the sandbar, the rudder was broken off, effectively making the ship useless.

The valiant crew of the Invincible tried to lure the Mexican ships closer to shore to improve her fighting position. In the process, the ship ran aground. The crew escaped but during the night, high winds and waves battered the once noble vessel to pieces. The Brutus never again left the Navy Yard. The Brutus was lost between October 3-5, 1837 during one of the worst hurricanes in the history of the Gulf of Mexico, named Racer’s Hurricane. That marked the end of the first Texas Navy.

Secretary S. Rhoades Fischer was berated by President Houston and forced to resign. Commodore Thompson was ordered to face trial under various charges. However, by law, his jury was required to contain three of his peers of equal rank. Since there were no officers of equal rank, the trial never took place.

Based on military standards, the Yucatán cruise had been an unquestioned success. As one historian noted,

For damage inflicted on the Mexican Navy, shipping, and coastal towns, including the raising of the Lone Star flag on Mexican soil, the Texas Navy, with its tiny two-ship fleet and daring sailors, under the leadership of Commodore Thompson, would become known south of the Rio Grande as “Los Diablos Tejanos" or The Texan Devils.

In 1839, the Republic of Texas formed a new navy with very close ties to the Republic of Yucatán, but that is another story.

Note from Byron Augustin, Author

Each time that I research and write a story that is mostly historical, I am reminded of the old adage, “History is what historians write.” I have tremendous respect for historical writings and their authors, but I also know that mistakes are made. For the research that I completed for these two articles for Yucatán Living, I found numerous errors in historical literature. One author states that the Maya ran into the mountains while escaping those Texas Devils. Anyone with knowledge of the topography of the Yucatán Peninsula knows there are no mountains to run to, unless you are prepared to sprint to Guatemala. Another author writes that Lorenzo de Zavala was born and educated in Spain, which is not correct. Death counts from military battles, especially during this period of history, were notoriously inaccurate. Many times armies underestimate their losses while overestimating their kills. At the Alamo, Santa Anna listed his mortalities at 300, the Texans said they killed 600, and one historical author gave a death tally of 1,000. In more recent times, the U.S. military drastically overestimated the daily body counts of the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

In reviewing and comparing the logs of Commodore Thompson and Captain Boylan, I found significant differences in their final reports. Commodore Thompson was at a distinct disadvantage, as his official log was destroyed along with the Invincible at the entrance to the Texas Navy Yard at Galveston. As a result, he wrote his final report from memory, while admitting that dates and names of towns might not have been accurate. Still, I have read historians who quoted Thompson’s log verbatim and as established fact. Finally, stories written by a Mexican using historical articles written by Mexicans in Spanish would produce different results. We hope the reader will keep these issues in mind while reading the articles. I tried to be as accurate as possible while relating what I think is a significant historical period for Mexicans, Texans, and Yucatecans.

I would like to thank Mr. Michael Bailey who has taught Texas History at Omar Bradley Middle School in San Antonio for many years. He is an outstanding classroom teacher who has won many teaching honors. He has also developed the Mills Cabin Texas Learning Center, where Texas fourth graders learn Texas history in a hands-on environment. The Daughters of the Republic of Texas have recognized him as the Texas History Teacher of the Year. Mr. Bailey graciously reviewed this article and suggested changes where errors or omissions were made in the original drafts.

*****

Read Part One of Yucatan's Connection to Texas here.

Comments

Juan Kantil 8 years ago

Very useful articles. The humility of your disclaimer is refreshing. Gracias.

Reply

(0 to 1 comments)