Paseo de Montejo Statues

The Statues Emerge

As hurricane season dawned in Merida, we noticed that workers were gathering each day at the remate, (the south end of Paseo de Montejo), building something. At first we thought they were building a fountain. Then, as the pedestal took shape, it became apparent that they were building a statue pedestal similar to the ones farther north on the avenue that supports statues to Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Dr. Justo Sierra and near the Gran Plaza, Gonzalez Guerrero.

Then one day, there were statues there, but they were veiled.

Fade out statues, fade in Bicentennial/Centennial countdown clock even farther north on the same avenue, reminding everyone that there are only 54 (or whatever) shopping days until the twin celebrations of 100 years since the Mexican Revolution (against the reigning oligarchy) and 200 years since Mexico's Independence from Spain this year. The countdown clock reminder is one of many scattered throughout Mexico in every city of any size, as this is a nationwide celebration. We would draw parallels to the Bicentennial celebration in the United States a few decades ago, with its fireworks displays and red-white-and-blue mania. But the parallels would go hyperbolic at this point because not only is Mexico celebrating TWIN centennials, but no one knows how to throw a party like Mexico. Yes, we know that could be taken as stereotyping, but we'll make an exception in this case because in Mexico, fiestas are the national pasttime.

Now, you may have noticed that these centennial celebrations tend to be celebrations in honor of Lady Liberty. Certainly, the American Bicentennial was all about throwing off the shackles of monarchy and celebrating 200 years of freedom and democracy. Here in Mexico, the celebrations will be about freeing Mexico from Spanish colonial authority and, 100 years later, freeing Mexicans from the autocratic rule of Porfirio Diaz.

Viva México! Viva La Revolución!

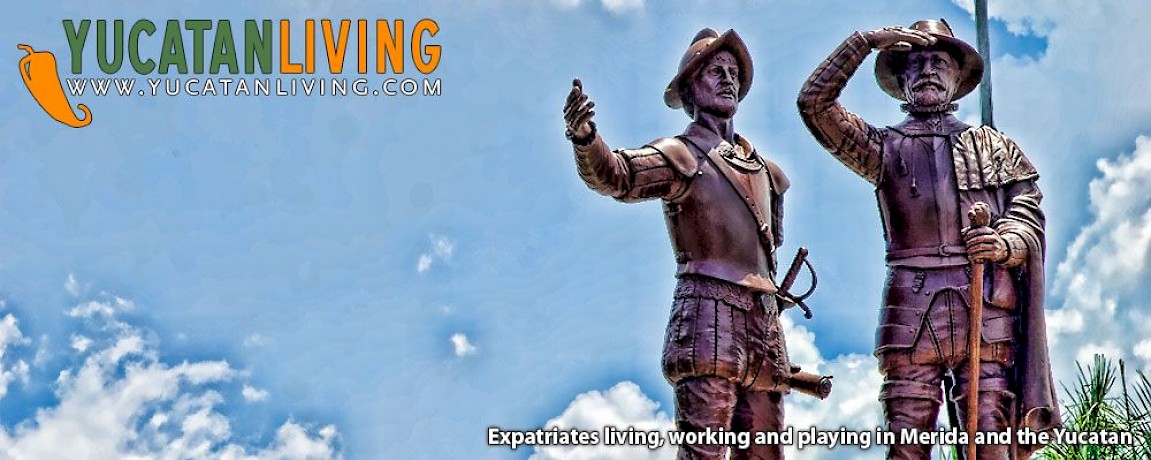

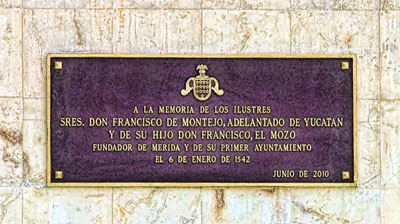

So imagine our surprise when the only statues erected in Merida this banner year, in one of the most visible and central spots in the city of Merida, in the year of the twin centennials, turned out to be fairly realistic renditions of old Francisco de Montejo himself and his son of the same name, together the two conquistadores who conquered the Maya city of T'ho and renamed it Mérida in 1542 after a city in their home country of Spain.

The statues were sculpted by Reynaldo Bolio Suárez, for a purported cost of $143,485.96 pesos (give or take a centavo). If you disregard the political overtones of the work, the statues themselves are professionally done and some of the best work on public display in this city (we would argue that the statue of Pedro Infante on Calle 90 is much more interesting). The details are well-crafted and the figures are well proportioned, though they strike us as a bit small in relation to the pedestal on which they stand, which could be seen, perhaps, as a veiled commentary on the regard in which they are held and how it may or may not be deserved.

Why Them? Why Now?

The question burning in everyone's mind, however, is why? Why these guys? And certainly, why now?

Our research turned up the facts that a local historian, Juan Francisco Peón Ancona, was instrumental in convincing the outgoing mayor of Merida, Cesar Bojorquez, to erect these statues. He was aided by the Patronato Prohistoria Peninsular, a group of citizens who take personal and professional interest in the history of the Yucatan Peninsula. These citizens all felt that a statue should be erected to the man or men who they say founded the city of Merida, but who also were responsible for building many of its major architectural attractions, and after whom the main avenue on which they stand is named. It seemed to them a gross error that a statue of these adventurous men was missing from this city.

Again, we can imagine that this took years to produce, and perhaps the timing of the end point of the entire production was not well thought through. In our minds and heart, we can cut them some slack.

We also know that many years ago, on the quatrocentennial of Merida's founding as a city (1942), the government erected a statue of Nachi Cocom (an important Mayan ruler at the time of the conquest) on this same avenue, and the avenue was renamed after him. At that time, apparently, there was a big uproar and, according to historian Peón Ancona writing in the Diario de Yucatan, "The rejection of the public was immediate and unanimous ... (I still) remember those "brand new" concrete monoliths with the name of indigenous leader, shot down in the night, on the Paseo, with ropes and chains, groups of boys and even older people, in manifest and clear rejection of the unfortunate disposition of local government". Apparently, some people were upset.

A distant acquaintance of ours, Genner Llanes Ortiz, a Yucatecan who is currently living in Brighton, England and recently completed his PhD in Anthropology at the University of Sussex, calls for an end to this monoculturalistic attitude on either side of the proverbial fence. He feels it is time for Merida to truly embrace its multicultural roots... and that perhaps these statues are not a good start in that endeavor.

Backlash

Certainly, the response to the statues was swift and vituperative on the part of many. First, there were the personal reactions. "Did you see those statues?" and "What were they thinking?", "Why would that do that this year of all years?". And these were just some reactions of the extranjeros that we know... perhaps our Yucatecan friends are too circumspect to vocalize their response quite so quickly or obviously. Although, to be honest, a lot of well-heeled Meridanos probably didn't even see the statues for weeks, as they rarely travel to the Centro. But we saw them right away. And so did the working class of Merida, the Mayans visiting from the pueblos and the students and other youth that congregate in the universities, colleges and coffee houses downtown.

A protest was scheduled a few weeks after the unveiling. The day after the protest, hand-written signs hung on the statue base, punctuated by paper maché feet and hands, painted white and red to symbolize the bloody hands and feet of the Mayan workers in the henequen fields. A week after that, a group gathered and presented a formal letter to the Ayuntamiento (City Hall) of Merida. Among other things, the letter pointed out that the arrival of the Spanish to the land of Mexico brought death and cultural destruction to the people living here, that this behavior should not stand as a model, that the invasion of the Yucatan was particularly violent, that the Constitution of United Mexican States decries discrimination of any kind, and that the same Constitution establishes Mexico as a multicultural country. The letter also points out that the local Yucatecan Constitution provides that Yucatan is a multicultural state, based on the indigenous Mayan people, and that "in this context to erect a statue to two of the most bloodthirsty invaders who Yucatan history has known... is an act of propaganda of racism and discrimination that our fundamental laws prohibit...". The letter calls for the immediate removal of the statues, as well as the appointment of a woman to one of the four cronista posts (official historians of the city, now all held by men), that the city put out a call to all the citizens of the city to see who they want a statue of, to rename the avenue to Bicentennial Avenue and that the city honor and celebrate ALL of the inhabitants of Merida-T'ho in this important year.

Where The Statues Still Stand

To this day, the statues are still standing, overlooking the vast avenue named after the men they pay tribute to. The outgoing mayor approved the building and erection of the statues, erected less than three weeks after the new mayor took office.

The new mayor is a woman (Angelica Araujo Lara) and of a different, more liberal political bent than Cesar Bojorquez, the previous mayor. Perhaps she will pay heed to the letter, and the people who undoubtedly voted her into office. Or maybe, she will not fight this battle, letting the more entrenched powers that started this process have and keep their statues where they want them. There are few statues erected in Mexico to the conquerors from Spain. Maybe Merida will buck the trend, and maybe it will not.

We are part of the multicultural city that is Merida. On principal, we support multiculturalism. But in this battle to declare who the true founders were of Merida, and who should be remembered, commemorated and put on a pedestal, we must remain on the proverbial sidelines.

*****

See the full text of the letter presented to the Ayuntamiento here. (translated with the help of Google Translate)

See an image of the letter with signatures here.

Article by historian Juan Francisco Peón Ancona in the Diario de Yucatan (translated by Google Translate)

Detailed and well-researched blog by Genner Llaner Ortiz, native Yucatecan and PhD in anthropology, recently graduated from University of Sussex in Brighton, England (also translated by Google Translate)

The recent AP article about the statues.

Comments

mcm 15 years ago

I'm glad that YL brought this topic up -- It's received a lot of coverage in the local papers, and the argument (which has received fairly even-handed coverage in the Diario de Yucatan) does provide an interesting window on the politics of culture (or the culture of politics) here in Yucatan.

For an interesting series of thoughtful discussions of this topic, in Spanish, I suggest that those interested read the posts from July and early August on the "Noticias de Merida" blog -- http://www.noticiasmerida.org/

PS -- I'm NOT suggesting that YL's article does this, but I do think there's a danger in equating the actions of a small group of activists (on either side of an issue) with "popular" opinion.

PS2 -- I do think that your characterization of the current mayor as "more liberal" than the outgoing Mayor is a little misleading (equating the PRI with a more "liberal" point of view than the PAN). Yes, the current mayor is more populist in her approach, but that's a different thing (in my view, anyway).

Reply

CasiYucateco 15 years ago

What an excellent summary of the events surrounding this statue. Or statues, as the case may be.

We foreigners may not fully appreciate the impact of Conquistador statues in Mexico.

But try to imagine:

A statue of General George Armstrong Custer erected at the entrance to a Souix reservation.

or:

A statue of King George III erected in front of the Washington monument.

And now, perhaps, you can see how this would be offensive.

In Mexico, generally speaking, the Conquistadores are not celebrated. They brought death to over 80% of the existing Mayan population within a few decades. Elsewhere in Mexico, the mortality rates were just as bad.

It could be argued that the Montejos did not "found" Merida. It was already in place as the Mayan city of T'ho (various spellings exist). What the Montejos did was to set up camp among the pyramids, fight a few fixed battles which -- in their words -- thousands upon thousands of Mayans were killed with the help of their alliance with a local (T'ho) leader, and then tear down the pyramids to build their homes, government buildings and churches.

The Montejos forged an alliance with Ah Dzun Xiu, ruler of the Tutal Xiu (from Mani, the present day city) to fight Nachi-Cocom. Years earlier, Ah Dzun Xiu's great grandfather had set up an ambush to slay the last ruler of Mayapan, the great grandfather of Nachi-Cocom, so it is safe to say this was a long-standing rivalry. The hatred was fueled by Xiu's alliance with the Spanish. In Otzmal where the Xiu had been granted safe passage to worhsip the mayan gods, after four days of feasting and worshipping, the Cocom slayed the entire Xiu delegation. They exacted revenge for the old wrong against the ruler of Mayapan, but sealed the fate of the Mayan resistence to the Spanish.

After these events, more Xiu became allied with the Spanish. Even though they were few in number, traditional Mayan forms of battle were no match for Spanish firearms, armor and horses. Backed by thousands of Xiu, the Spanish eventually defeated the Cocom. Although resistence continued to various degrees, coming to its height during the Caste Wars of the 1800s, the Spanish effectively subjugated the Maya at that point.

So, looking back those 500 years or so, you can see the Spanish alliance with the killers of the last great ruler of Mayapan -- in turn the last great Mayan city -- fueled harsh feelings that perhaps continue to this day.

Even without this historical note, the arrival of the Spanish signaled horrific times ahead for the Maya, whether they were allies or opponents of the Spanish. The Inquisition soon arrived from Spain and the horrific tortures associated with that pogrom were instituted by friars, monks and priests.

Raising a statue to commemorate the people who brought these events upon the local inhabitants is understandably controversial, to say the least.

Reply

« Back (10 to 12 comments)